Dr Wong Chiang Yin is no stranger to most in the medical profession. Throughout his career in medicine, he has held many leadership positions including Group CEO of Thomson Medical Group, Group CEO and Executive Director of Cordlife Group Limited, Chief Operating Officer (COO) of Changi General Hospital (CGH) and Singapore General Hospital (SGH), and Director of the Projects Office of Singapore Health Services (SingHealth) and Assistant Director in the Ministry of Health (MOH) of Singapore. He also sets aside time to volunteer for the profession and has been on the councils of both the Academy of Medicine, Singapore (AMS) and SMA for more than two decades. In fact, he will be receiving his 30-year SMA Long Service Award in 2025! Dr Tina Tan (TT) and Dr Clive Tan (CT) take this opportunity to speak with Dr Wong Chiang Yin (WCY) to find out more about his life journey and his vision for medicine in his new role as the Master of AMS.

Formative years

CT: Thank you for accepting our invite for this interview, Chiang Yin. Perhaps you could start by sharing a little about your family background. Where do you think your story starts?

WCY: I came from a typical Singaporean family. My parents were both non-graduate Chinese teachers, and I grew up in a HDB flat. I did well enough in school to be in the Anglo-Chinese School (ACS) top class and I joined the science quiz team where I hung out with many people who were science geeks. At Anglo-Chinese Junior College, I got into triple science and followed the crowd where I applied for medicine. It is quite a boring story.

CT: Was ACS then a very elite school, and was it tough for you coming from a humble family?

WCY: In those days, there were two primary schools. The one I went to, Anglo-Chinese School (Primary) (ACPS) was on Coleman Street, which is where the National Archives is now. The Anglo-Chinese School (Junior) (ACJS) was at Barker Road. If you asked me, there was probably some class divide when we merged in Secondary 1. Oftentimes, the poorer students came from Coleman Street, and our Chinese was generally better because we probably did not speak much English at home. In those times, we spoke mostly dialect.

CT: Did that grounding in your childhood affect your journey in medicine and subsequent career?

WCY: My parents did not give me any serious career advice. They just said to not be teachers. (laughs) I was once invited to deliver a career talk in ACJC. There was another old boy, a lawyer, present, so I jokingly said to the students that medicine was still worth going into because we at least get mentioned in obituaries. Nobody thanks their lawyer or accountants when they die. When I said that, the lawyer looked at me and gave me a dirty look. He had no reply.

TT: He was probably agreeing with you in his mind. [laugh] What was medical school like for you then?

WCY: I took a detour because I did not get any National Service (NS) disruption. Instead, I went to the Singapore Armed Forces and served my NS as a storeman, which turned out to be a very important detour even though I was very disappointed at the time. That time in NS taught me how to speak Hokkien (local dialect). If you had met me before I was in the army, I could probably only speak less than five words in Hokkien. But I picked it up during the time spent with other storeman, cooks and drivers. I even taught cooks English in the army. I learnt Hokkien because I needed it to survive in NS and it did me a world of good because when I became the COO of SGH in 2001, Hokkien came in very useful. As the COO, I often had to talk to the housekeeping, security and maintenance staff or facility and plant technicians, as well as cooks, and having some Hokkien in my communication with them helped me build rapport.

TT: What happened after medical school?

WCY: I felt I was behind time and did not want to specialise initially as I wanted to catch up. My father had passed away during my second year of medical school, so there was some urgency to make money, at least from my perspective. At around that time, I received a phone call asking if I would like to join the MOH Headquarters in their new Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) Department set up to regulate TCM practice. They had just issued a report on TCM and they needed to set up a regulatory department and to pass TCM-related laws in Parliament. I thought to myself, “Why not? Just give it a shot.” There, I had to learn how the Ministry worked and also the basic principles of TCM. I spent two and a half years in the department.

Embarking on apprenticeship

CT: So, you moved on to the administrative side rather early in your career.

WCY: Yes. I found it very interesting while I was working there and applied for public health traineeship.

CT: Who were your public health seniors at that time who kind of advised you and talked to you? Did they encourage you and shape your thoughts around public health?

WCY: There were people like Drs Chew Ling, Jason Yap and Jason Cheah at that time. Life was very simple then. We just had to think about passing the interview and get chosen. The same batch of trainees who applied with me were Drs Kok Mun Foong, Chan Boon Kheng, who runs a hospital group in Malaysia, Tan Sze Wee and Pwee Keng Ho. I worked for six months as a non-trainee and applied for traineeship after six months. I had considered family medicine as well, but I did not think that I could have made a good surgeon. During my first week of the posting with the Orthopaedics department where I was in the spine team, we were scrubbed up for 12 hours with only a break in between for lunch and bathroom as we worked on fixing the spine of a patient who had attempted suicide. I was in the operating theatre for the whole day and came out only about 9 o’clock. This experience made me realise that I was not cut out for surgery.

CT: What was your traineeship journey like?

WCY: I talked about that and apprenticeship in my October AMS Master’s Message. In today’s context, I probably would not be able to exit. In my six years or so of training, I only had one supervisor who was a public health specialist, and that was Dr Ho May Ling. All my other direct supervisors were not trained in public health.

My first boss was Dr Wong Kum Leng, a plastic surgeon and a Chinese-educated Chung Cheng High School top student who was a very tough boss, but I learnt a lot from him. After that, I worked under Dr Ho May Ling, my only public health specialist boss, in the Medical Accreditation and Audit Unit, which is the precursor to the Licensing Authority of Health Regulation Division under MOH. Of course, there was the Director of Medical Services, Dr Chen Ai Ju, but she was not my direct boss. I then went into my one-year full time study at the National University of Singapore for my MMed (Public Health) and when I came back, I worked for Dr Mimi Choong, a non-specialist doctor (immediate past CEO of the Health Sciences Authority), for a while. After that, I worked for Ms Chang Hwee Nee (current CEO of National Heritage Board), before I joined SingHealth and worked for Prof Tan Ser Kiat as Director for Projects Office when the clusters were formed. I then moved over to SGH as Director of Operations, where I reported to Dr Vivian Balakrishnan, before working for Prof Ong Yong Yau as COO after Dr Balakrishnan went into politics. And then SARS came. In 2004, I went to CGH as its COO, reporting to Mr TK Udairam before I exited my traineeship.

The irony of it is that I am an accidental specialist. When SARS struck, there was no one with an MMed in Public Health in SGH. I was appointed as the de facto Chief Epidemiology Officer by default upon the outbreak in Ward 57 and 58. In those days, we had to meet the press, which included international press, such as BBC and CNN, as well as local press and Mediacorp, every other day across the road in MOH with then Minister Lim Hng Kiang and senior MOH staff. When the outbreak occurred, I had three days to discover who the index case was. I went through all the records and investigated before I presented in the MOH board room and stated who I thought was the index case based on place, person, time, etc, and all the information available. After that presentation, Prof Goh Kee Tai tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Chiang Yin, now you’re a real public health specialist.” And I replied, “Actually, Prof, I haven’t exited yet.” I could still remember the look of surprise on his face.

After the SARS outbreak, I underwent training supervised by Dr Jeffery Cutter and Dr Shanta Emmanuel and wrote my paper. In those days, you must publish a first-author paper to exit and so I published one.

A drive to advocate

TT: In which year did you exit?

WCY: It was 2006, the same year that I became SMA President. Later on, Prof Fock Kwong Ming, who was the assistant Master of the AMS as well as the chairman of the medical board of CGH then, told me that I must join the Academy, and I did. I joined the AMS Council in 2009 as I was stepping down as SMA President.

CT: Your SMA journey began much earlier then?

WCY: Yes, I joined SMA just one month before housemanship ended. I was in the SMA Medical Officer (MO) Committee, the precursor to the Doctors-in-Training Committee, where we were fighting for housemen call allowances. There were five of us ACS boys who got together – two from the ACJS in Cairnhill and three from the Coleman Street ACPS side. The ACPS boys were Dr Tan Sze Wee, Dr Yue Wai Mun, a spine surgeon now working at Gleneagles, and me. The other two were Dr Wong Tien Yin and Dr Goh Jin Hian.

The five of us worked out the numbers and we published a survey which was caught by the press. It was published in the New Nation paper saying, “Houseman paid less than McDonald’s waiters by hourly rate”, and we got summoned for coffee.

CT: Was that in a way your first foray into advocacy? Do you think that shaped your views?

WCY: Yes, always, because we were thankfully successful. Housemen were paid nothing for calls, nothing. MOs were paid $40 for one call, after the fourth call. Only at the fifth call, would you get $100. As such, everyone wanted to do five calls, because for that you are paid a magnificent $260. And for housemen, the call allowance went from $0 to $70, which was a big thing! We were very fortunate to have an understanding director of manpower, Dr Clarence Tan, who was also a forensic pathologist. However, the five of us did not get to benefit from it personally because we had already exited that phase by the time it got through.

CT: How did that positive experience coupled with the drama of being called up for coffee shape your world view?

WCY: I am an optimist – I believe that change is possible. And I believe that we do not have to be too confrontational to effect change. Sometimes you need a little bit of timing, with the right people around.

CT: Are there any memorable incidents in your very long career?

WCY: SARS was one of them, where people, including my second cousin – Dr Alexandre Chao, died. In a way, SARS was deadlier in terms of case-fatality rate. There were people who would say that they did not want to go into the SARS ward, but I told them, “This is what you signed up for when you became a doctor.” Before SGH had its own cluster, we deployed one ICU team at Tan Tock Seng to assist. In those days, you help each other out and at the end of the day, we pulled through.

CT: How about memories from your time with SMA?

WCY: The most memorable thing was a very sad one. A law was passed rendering our Guideline on Fees a potential contravention to the Competition Act, and we had to withdraw it in 2007. Years after, we saw the negative ramifications. MOH has since stepped in with their own fee benchmarks, but it is not quite the same.

TT: When you look back at all these years, how do you feel your own personal vision with your work fit in with the various people and organisations you have worked with?

WCY: Personally, I am always prepared to walk away from my work. I may be fat, but I travel light. I have no family or kids. I can always walk.

CT: I suppose that gives you the courage to say difficult things.

WCY: Yes, somebody once said that I have this propensity to periodically make career-ending remarks.

CT: Do you feel better after that though? Like you can sleep better?

WCY: At the end of the day, I believe that the world is fair and that most people know what you are doing is not for yourself. I think that is very important, that you are doing it for a cause, for the better good – for the profession and for the patient as well.

Challenges in modern times

TT: Do you think professional bodies are still relevant to current and future generations?

CT: Also, what is your reason for taking on this very difficult and sometimes thankless role?

WCY: We have to ask ourselves the question why we are even here. I mean, I could be elsewhere enjoying myself instead. However, I have always believed that I want to leave the place in a better shape than when I found it. With every organisation I join, I will probably leave some mess behind, but I would likely have cleared more of a mess than what I leave. That is the essence of management and administration.

I think overall expectations were lower in my generation, so it was easier to satisfy people’s material expectations. It is likely more difficult for the younger generations because their experiences are different. For example, if I were alone, I would probably be sitting in some hawker centre in my bermuda shorts and T-shirt, having my kopi o kosong for $1.30 and a bowl of noodles, which I will be a bit more extravagant and ask for an upsize, for about $7. But nowadays, many young people will drink coffee in some nice posh place where it costs $5 or more for a cup. If your default option of drinking coffee is not in a coffee shop, you will obviously have a higher cost of living. On the other hand, the countervailing force is that doctors are getting more and more common. When I became a doctor, there were probably about 5,000 doctors in Singapore. According to the Singapore Medical Council’s (SMC) 2024 annual report, there are now 17,466. As such, there is less of a rarity effect today and no scarcity value, to put it in economic terms.

TT: What does that mean for your own vision, especially when it comes to advocacy?

WCY: Intrinsically, the Academy is an academic body looking into the professional development of specialists in skills and knowledge. However, I do believe that without giving doctors the proper practice conditions, it is very difficult to enable the academic pursuit of knowledge and skills. They are linked. We are not talking about human beings with no needs, so we must give doctors the chance to make a good living such that they can satisfy themselves materially to a reasonable extent. At the same time, doctors will have to continue in their academic and professional pursuits. It is like a chair with three legs – you cannot saw off a leg and hope for the best.

Today, there are some doctors who may ask, “Why must I be part of any professional bodies to enjoy free mandatory medical ethics (MME) training? Why must I pay?” But the point is not about MME – MME is a red herring. If one has been a doctor for say ten or 20 years and yet sees no need to be part of any organisation or any professional guild, then the problem is with the person.

Among the traditional professions, law and medicine are professions that were started and maintained by professional guilds. Medical schools came later, with universities coming in even later after medical schools were incorporated as part of the university. I can understand when one is a young doctor, yet to decide on his/her specialty and career, choosing to not join the professional bodies. But if these doctors have graduated for decades and yet take pride in that they are not part of any professional bodies, then they do not actually understand the profession they have signed up for.

CT: I love that. I have talked to so many people about this and you are the first person who have said this in such a succinct and powerful way.

WCY: Doctors cannot work in silos. We can argue that some professional bodies are not giving you your money’s worth. Yet the key thing is not about giving you your money’s worth, but how much you can contribute. And it is quid pro quo. The guild must contribute to you, and you must also contribute to the guild.

For professional bodies like the AMS or SMA, we must always stay relevant. Because if a professional body is not relevant, then as I have said in my first message as Master, you can close shop. This is exactly what happened to the New Zealand Medical Association which has tutup (Malay for shut), or in Cantonese we say zap lap. They were started the same year as ACS – 1886, more than a hundred years old yet they closed shop just a few years ago. That is serious, so yes, I can take criticism that some professional bodies and guilds are not relevant, and indeed some have not been relevant and have gone the way of the dodo. But if you say, “I just don’t want to belong to any body, whether you are relevant or not,” then I think the problem is with the person.

Stepping into the role of a master

TT: How can professional bodies stay relevant then?

WCY: First, you must understand your constituency. In essence, professional bodies have certain union-like characteristics, and where there are elections, there are also certain political characteristics, because there is the body of voters that you will have to appeal to. The question is whether you can do the right thing, not be a populist and at the same time remain relevant?

CT: For you to dedicate the two or maybe even four years of your time to serve as Master of AMS, what are some of the driving forces that prompted you to stand for election?

WCY: Internally, I want to look at how to reorganise the way AMS is run. I am a bit different from most other Masters, after all. I am neither a clinician nor an academic. I am just a guy who hangs around at the right time, maybe at the right place… but I do have some business experience. That is why I would like to look at how to restructure things in the internal workings. Certain things I cannot divulge yet, but I have submitted some proposals to SMC for their consideration. Externally, it is always a challenge. AMS is very different from SMA. SMA is one body, whereas Academy is tiered and more like a federation because each of the colleges run themselves. In fact, there are 13 colleges, some with chapters under them and six chapters directly supervised by the AMS council. There is a structural difference, so we must accept the difference and that things may move at a slower pace.

The AMS secretariat is also a very complicated setup because they serve so many colleges. In SMA, the secretariat only serves 20 people (the SMA Council). In AMS, we have more than 20 Chapters and Colleges, each one with their own council. One thing I learnt even when I was working in SGH and the Outram Campus is that complexity is not additive, it is multiplicative. With the multiple departments involved, complexity is not just 1+1+1+1+1 = 5 but is a multiplication of five. It is in fact 5x5 = 25, as each department must coexist with the other four.

CT: Since this is such a big mountain to move, I can understand why people may choose to not tackle the big monsters.

WCY: I am not here to tackle the big monsters either. In my old age, I rather also live peaceably, but I will do things that I think should and can be done. For things that you know cannot be done, there is no point in pursuing those.

CT: So, you have to be selective and prioritise.

WCY: Yes, fight the battles that you think are worth fighting and that you can win.

CT: What are some of the values that you hold strongly as AMS Master?

WCY: I believe that apprenticeship is important. One way of expressing it – and if you are a Star Wars fan, you will understand – is that whether you are a Jedi or a Sith, there is a relationship of apprenticeship involved.

That is why I would say that during my traineeship, what I had was apprenticeship more than training. If you were to think about the bosses I listed earlier, they technically cannot be my trainers by today’s standards. Today, to train someone in public health, you must be a public health practitioner, and to train a psychiatrist, you must be a psychiatrist. However, I had people of various specialties and experiences providing me with apprenticeship and training me during my early days; it may be unstructured training, but I think I did not turn out too badly – I survived. That is of course, possible for public health because it encompasses general skills and such. Even today, the School of Public Health is not chaired by a public health physician.

TT: Given your concerns about residency vs apprenticeship, how do you marry the two since residency is already in place?

WCY: Residency does serve a purpose: it ensures a certain quality with volume. It is also scalable, but it comes at the cost of a lot of paperwork and the challenge of addressing how one learns the art of medicine.

CT: I want to pick up on that point, because the apprenticeship is premised on relationship and a sort of compact.

WCY: Yes, the compact involves modelling and mentorship. We as apprentices learn by modelling (ie, I model after my boss), whereas mentorship is the master trying to mould you, the apprentice. It is a two-way relationship, with two terms for it. When I went through the stacks of documents regarding specialist training requirement however, it did not mention anything about mentoring or modelling.

To be fair, I do not have a solution either. Ideally, if you get a good mentor, you are in good hands. But if you get a bad mentor or you simply do not get along with him/her, it will be much more challenging. It is thus a touch-and-go business, and it cannot be scaled. When I was a trainee in the 1990s, there were only a handful of us and everybody knew everybody. These days, every intake is approximately 700 students, so there are 300 traineeships a year. Multiply that by six (ie, six years of traineeship), that makes 1,800 trainees.

For example, just in the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) alone, do you know how many fully qualified psychiatrists there are? There are 109, give or take a few at any one time. And we ask ourselves this, other than perhaps the CMB, would as an associate consultant or first-year consultant know all 109 psychiatrists? This number does not even include the residents, the nurses and the MOs. That is how big the system has gone.

CT: I am going to be provocative and ask if we are being nostalgic here. Just like how people are nostalgic about HDBs and the kampung spirit, but it is a one-way street. Are we therefore pining for something that is long gone?

WCY: Well, as an old man, I am entitled to pine and indulge in some nostalgia. Having said that, yes, we cannot go back to the old days. However, a world that is purely transactional, and not based on relationships and professional norms and values is also probably not a good place to practise medicine. And if we run a training system based on checklists without much emphasis on relationships, professional norms, guilds and behaviours, it is perhaps also a very radical and risky premise to work on

CT: If I may build on that, in a way, when we adopted the residency system, there were some side effects and trade-offs to enable the scalability of it.

WCY: Yes, I agree that there are trade-offs but if one goes in with eyes wide open and is prepared for the losses, that is fine. However, the reality is that one probably loses something inadvertently in the process.

CT: That is a good message about policymaking, because we shape policies and advocacy through our actual work, but we often do not talk about the trade-offs.

Foodie, author, historian

TT: Now that we are done with the heavy questions, I would like to talk about your food columns.

WCY: I was born fat and I grew up fat. [laugh] I am Cantonese and we are very obsessed with food. Did you know that there is a common injunction in Cantonese households? When mothers tell you to “fan lai she fan” (Cantonese for “come home and have dinner”), it is different from “fan lai yam tong” (Cantonese for “come home and have soup”). Soup is very important to the Cantonese. It is still relatively fine if you do not go home for dinner, but if your mother says to come home for soup and you do not turn up, you are in big trouble.

It is an injunction, unlike an invitation for dinner. When they ask you to come home and have soup, it means that they have boiled the soup for a good six to eight hours, and you better make it home. When you say, “lou fo tong” (老火汤), it means boiling for a minimum of four hours. That is very important.

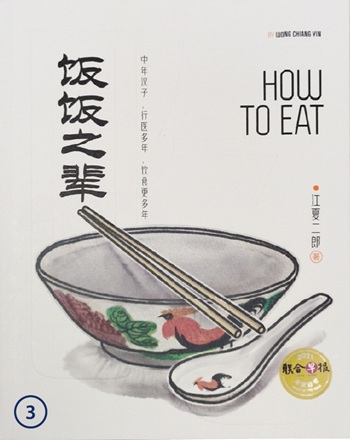

Anyway, I wrote for three and a half years for Lianhe Zaobao, from 2016 to 2020 or so. Then the pandemic hit and I had nothing to do. It was then that my friend Anthony Tan (then Deputy CEO of Singapore Press Holdings and current CEO of MOH Holdings) came and asked if I would like to publish the food columns as a book with English translations, and that resulted in my book How to Eat.

I am thinking of writing a chapter on Taiwanese food next. I go to Taiwan almost every year. It is very interesting in Taiwan where they have the 眷村 (military dependents' village) culture. Chiang Kai-shek had taken like a million troops with him and these little villages are ex-army camps that have developed their own cultures over time, and certain dishes are particular to this kind of culture. Even Teresa Teng grew up in a 眷村!

TT: Wow! What kind of dishes are unique to this culture?

WCY: These people were originally from all over China and are not Hokkien, so their dishes are not traditional Hokkien ones. Dishes like your Taiwan beef noodles (台湾牛肉面), egg rolls (蛋卷) and soya bean milk (豆浆) were not Hokkien food. Although now popularised as local Taiwanese food, these were brought in by the non-Hokkien migrants (外省人). Local Hokkien dishes would be the orh ah mee sua (蚵仔面线; Oyster mee sua). Did you know that Taiwan makes the best bonito (used in dashi stock)? When the Japanese ruled Taiwan, the first thing they did was build a bonito factory.

The place with the most cultural history in Taiwan is actually Tainan. Although Taichung is now the second largest city, Tainan was in fact the old capital of Taiwan during the Ming dynasty. Koxinga, also known as Zheng Chenggong (郑成功), was from Tainan. They have a fort there and they have one of the best street foods. Taiwan’s biggest night market, Hua Yuan Ye Shi, is also there. It is very fast and convenient to take the high-speed rail (HSR) from Taipei to Tainan. It only takes one and a half hours. It is almost the same distance between Singapore and Kuala Lumpur (KL), Malaysia. Taiwan is not a big country; from north to south, it is only about the distance of Singapore to KL, and likewise for South Korea. Busan to Seoul is only 320 km and Kaohsiung to Taipei is also only around 350 km.

TT: You have very esoteric knowledge.

Final thoughts

CT: Chiang Yin, if we were to ask you for advice for young doctors under 30s, what would it be?

WCY: My advice to young doctors is very simple. Medicine will give you a comfortable life, a rewarding life, but it may not give you the kind of material wealth that you see in the older generations. Some of them own bungalows, drive Porsches and such, but this will get harder and harder to achieve simply because of lack of scarcity value.

TT: And there is the cost of living too. Inflation.

WCY: Yes, that too. And if the job of a doctor is getting commoner and commoner, the growth may not match that kind of inflation. My advice is thus to not go and buy a bungalow or a good class bungalow only to try and fulfil your financial commitments by practising less than ethical medicine. Be happy even if you drive a less fanciful car.

TT: That is good advice. Thank you, Dr Wong!

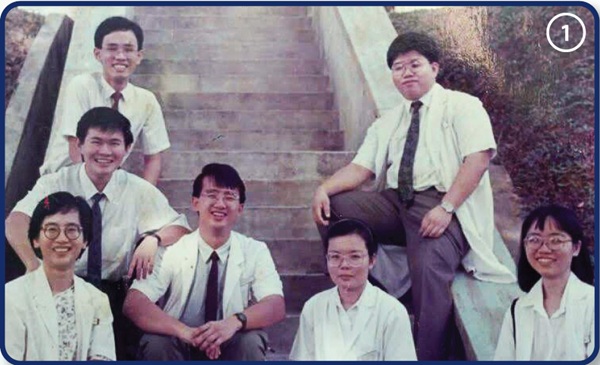

Dr Wong with his clinical group in medical school

As a 4 year old kid

How to Eat, by Dr Wong Chiang Yin