Healthcare workers (HCWs) and superheroes have not been so synonymous until this COVID-19 pandemic. Not only is being a HCW rewarding, it is also somewhat flattering to be called a superhero, to know that people are acknowledging the dedication and hard work we put into supporting the country through this crisis. It gives us the encouragement and motivation needed to push on. It also feeds into our system of altruism, which is essentially one of the fundamental values that our profession is built on. Altruism shifts our focus to "what I have to do for the greater good", away from "selfish things I need to do". But does this constant glorification of HCWs and our altruism have downsides?

The villain called "altruism"

Years ago, I came across the concept of pathological altruism which has been described extensively in the literature. One of those who had studied this was Barbara A Oakley, who described pathological altruism as behaviours where one attempts to promote the welfare of another or others, but it results instead in negative consequences to others or to the self. She found out that people with high levels of altruism also have high psychological problems including unhappiness, worries, fear, nervousness and somatisation. Indeed, it is unsurprising that caring for others could potentially lead to undesirable consequences if taken to the extreme.

Alongside this superhero image are the expectations associated with it. In the public's eyes, healthcare superheroes are always there and are always able to help, which then translates to our own need to live up to their expectations. When we start to identify strongly with this projection and emulate the superhero identity, the risk is that we push our altruism system into an overdrive mode, so much so that it becomes "pathological". An example of a pathological state is when someone constantly tries to go over and beyond to meet work demands – covering multiple duties, spending longer hours at work, not taking leave – and ends up spending most of their off days recovering from exhaustion at the expense of social activities. For many, the fight also does not end after work as we continue to take it upon ourselves to advise and encourage our friends and families on COVID-19-related matters. It is really no surprise that Peter Parker tried to quit being Spider-Man so many times.

Burnout is no stranger to us. However, when we look at its criteria, we may realise that we do not fulfil them. So we tell ourselves that what we are feeling is normal and that we are perfectly okay. It may be true that burnout rate is low among us, but that feeling of something brewing from deep within is not perfectly okay. That may be brownout – a term used to describe a period of reduced voltage of electricity usually caused by high demand and which would result in reduced illumination. Business analysts subsequently used it to describe the phenomenon of a deeper and more obscured type of fatigue that tended to present in high performing individuals. Burnout is typically characterised by exhaustion, depersonalisation and reduced personal accomplishment leading to mental health issues, lapses in work and people leaving their jobs. In contrast, someone with brownout is performing fine, in fact putting in even more hours at work, delivering the required results and saying all the right things at meetings, but they suffer in silence and out of sight. Due to its obscure and chronic nature, perpetually staying in the brownout stage and not crossing the threshold into a more noticeable burnout stage leads to more considerable long-term problems – physical deterioration, self-care neglect, strained relationships with family and friends, reduced personal interest and emotional disengagement at work.

The hero called "selfishness"

Altruism and selfishness are natural antonyms because of the core characteristic of the former - being selfless. If pathological altruism is a problem, perhaps "selfishness" is a solution. In 1939, Erich Fromm criticised the cultural belief that selfishness made people feel guilty about showing themselves healthy self-love. Subsequently in 1940, Abraham Maslow argued for the need to distinguish between healthy and unhealthy motivation for what we perceive as "selfish behaviour". This theory of "healthy selfishness" was subsequently widely discussed, and it could be understood as the need for us to prioritise our needs and well-being without feeling guilty about it. The fine line that puts it in the "healthy" spectrum is that it does not stem from a lack of consideration of others, but rather the primary motive of self-care in order to be able to continue to contribute back in the long run.

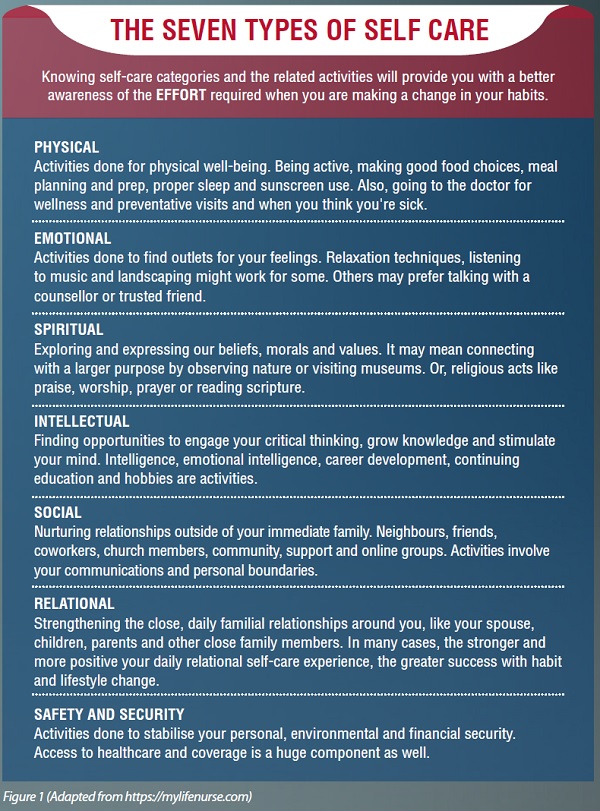

So stop telling ourselves that "I can" or "I have to continue". Instead tell ourselves that "I can and I have to take a break for self-care". This means taking days off, requesting for work coverage, and not bringing your work and superhero identity home. Always remember to "de-gown" upon leaving. On days when working from home, make it a point to set a time to knock off. Don't check your emails over the weekends. However, if you really have to, set aside a fixed amount of time to do that so you still get ample time for yourself. Inform your colleagues or team in advance that you would not be responding to texts or emails after office hours and agree on the ways to contact you for urgent matters. Then use the time and mental bandwidth freed up to focus on your self-care (see Figure 1 for the seven types of self-care categories.)

As a peer and teammate, remind one another to practise self-care. Offer to take turns to cover one another's work and do not make anyone feel guilty about needing to take a break. Besides burnout, keep a lookout for brownout. With all the safe-distancing and safety measures in place, make it intentional to create alternative socialising opportunities within the team. At an institutional level, make information on and access to staff support services easily available. Be proactive in checking in regularly on how team members are doing instead of waiting for them to ask for help. Reach out personally to individuals whom you think may be struggling, so that they don't feel pressured to say that they are okay. Even if the reply is "I am doing fine", the act of checking in would already have an impact. In a nutshell, I quote and paraphrase a famous statement – if you don't love yourself, how are you going to love somebody else?

As doctors, we take what we do very seriously and we are committed to the profession and the craft. It is undebatable that we are all truly superheroes. But sometimes, we have to remind ourselves that we are also only humans after all. We are not always superheroes. It is okay to not be a superhero.