The SMA Centre for Medical Ethics and Professionalism (SMA CMEP) organised a webinar titled "Best Interest Principle – The Ethical Analysis and Application for Persons with Diminished Mental Capacity Webinar" on 24 May 2025.

One of the clinical scenarios discussed involved Mdm L, an eighty-year-old female patient with moderate Alzheimer's disease dementia, who had been admitted to the hospital for community acquired pneumonia. This was complicated by hypoactive delirium, and it was deemed unsafe for her to eat or drink orally. As a result, the speech therapist recommended a nasogastric tube (NGT) insertion, with the plan to conduct a videofluoroscopy to assess her swallowing when Mdm Lee became more alert.

Ethical dilemma

When this recommendation was shared, Mdm L's children highlighted that a discussion had been held previously about her healthcare and end-of-life preferences. Mdm L was not involved in that discussion due to diminished capacity, but the medical team had taken the family through an in-depth discussion about her beliefs, values and preferences.

Mdm L had always been independent and did not wish to be a burden to her children. The issue of NGT insertion was raised and her children felt that she would not wish to have one inserted if she developed swallowing difficulties. She had once seen someone with a similar tube and said, "It looks painful, I would not like that."

As such, Mdm L's family was uncomfortable with the notion of inserting the NGT as they felt they will be going against her wishes. The medical team, however, was concerned that if the NGT was not inserted for nutrition and medications, it could affect Mdm Lee's recovery.

What would be the right thing to do? We explore in the next sections the ethical analysis of this scenario.

Ethics in clinical practice

Ethics is a core and central feature of patient care. In day-to-day clinical practice, the doctor-patient relationship is predicated on key ethical principles including confidentiality, informed consent, respect for life and respect for autonomy. In most clinical situations, the care plans proposed are aligned with these ethical principles. However, on occasions where ethical responsibilities conflict, an ethical question emerges and the need for ethical analysis arises.

Ethical analysis is therefore a systematic approach of applying ethical theories, guidelines and principles to the clinical situation. Using critical analysis and reasoning, the goal is to arrive at a reasonable, justifiable and defensible course of action so as to achieve good patient outcomes.

There are several methods available for clinical ethical analysis:

Ethical analysis using the four-box approach

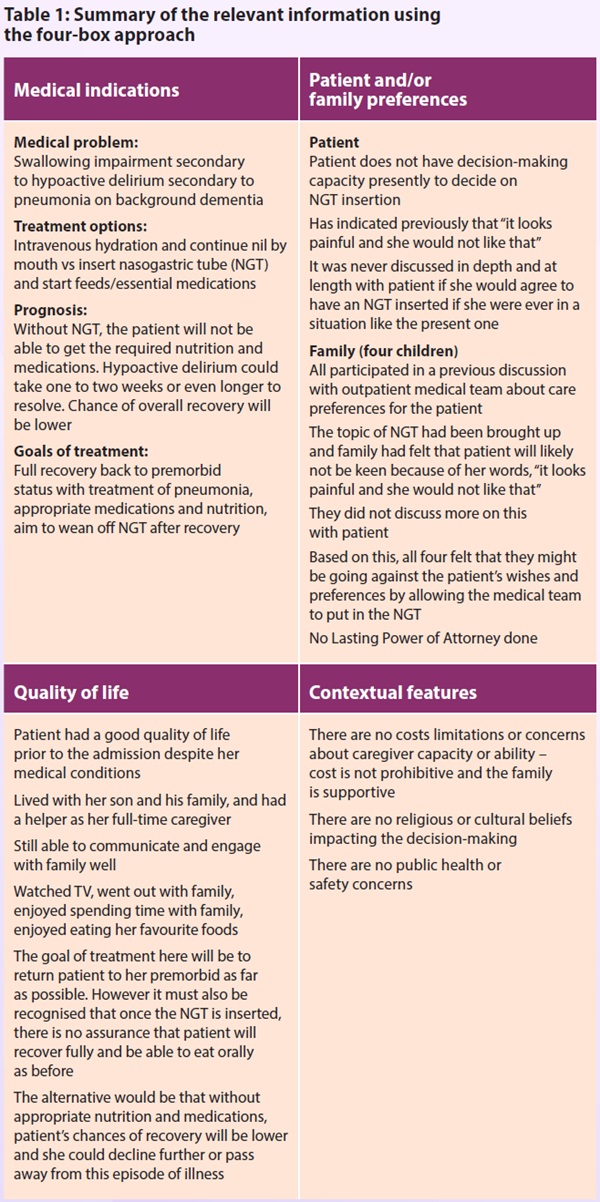

In this article, the four-box approach is used for the ethical analysis of the clinical case (see Table 1).

This approach involves the collection of relevant information from the case and categorising them under four topics. Each topic links the clinical facts to ethical principles and bridges theory and practice.

The four topics and corresponding ethical principles are:

Medical facts and indications

Mdm L has a history of moderate stage dementia with hypertension and osteoarthritis. Prior to the admission, she was able to ambulate independently and was independent in her activities of daily living with some supervision. She now has swallowing impairment secondary to hypoactive delirium as a result of an acute episode of pneumonia. The natural and proposed course of treatment is to treat the infection and optimise chances for recovery by giving her the medications and nutrition that she requires. With appropriate treatment, her prognosis is good.

However, Mdm L is unable to give consent for the insertion of NGT and her family is not agreeable with the procedure. The medical team is concerned as it is unclear when Mdm L will improve in her mental state; the longer nutrition and medications are withheld, the lower the chances of her recovering from a potentially reversible medical condition.

From the perspective of beneficence, inserting the NGT is appropriate to give Mdm L the best chance of recovery by giving her the medications and nutrition she requires. From the perspective of non-maleficence, the risk of inserting an NGT is low in the hospital setting. Therefore, inserting the NGT upholds both ethical principles.

Patient and family preferences

Mdm L has once said she would not want an NGT. It is however important to note that the context and the situation was a different one, and Mdm L did not explicitly say she would not want an NGT in a situation when it could potentially help with a reversible medical condition.

Her children agree that if she had made no mention of NGT to them, they would not hesitate to agree to the NGT insertion. However, in view of what their mother had once said, they do not wish to go against her will and are in a dilemma.

To uphold the principle of autonomy, if the patient had capacity, it will be crucial to share information with her so she can make an informed decision. However, in a patient without capacity, we will have to apply the best interest principle, taking into consideration her needs, values and circumstances.

The best interest of Mdm L in this situation is to aim for cure of the pneumonia with all the necessary medication and supportive procedures. This includes inserting a NGT to support her needs.

Quality of life issues

Mdm L's quality of life prior to admission was good, with her family describing her as being happy and engaged. What matters most to her is her family – whenever she was with them and spending time with them, her well-being was positive.

Other than dementia, she had no other life-limiting conditions. From the perspective of dementia, she had moderate stage disease and was not yet in the advanced or terminal stages. During this admission, there are also no signs suggesting new conditions that could limit her return to her premorbid status.

The insertion of NGT in this situation was therefore meant to be a temporary treatment measure, with the goal of giving the patient the optimal treatment to achieve a full recovery and return to her premorbid status.

Contextual issues

There are no costs limitations or concerns about caregiver capacity. There are also no religious or cultural beliefs impacting the decision-making. Neither are there any public health or safety issues.

Mdm L's family is keen to do all that is possible to help her recover. Her medical team also feels that she has a good chance of full recovery.

Analysis and recommendations

The ethical dilemma was related to a statement once made by the patient that contradicts the recommended treatment. However, with further discussion, it became clear that the statement was made in a different situation and circumstance. Any discussion on care must be interpreted in the context of the situation at hand and not considered as a blanket rule to be adhered to.

It is also clear that the patient had a good quality of life prior to the admission and that she had a good chance of making a full recovery if given optimal treatment.

In view of that, it is in Mdm L's best interests to insert the NGT to provide her with the nutrition and medications required. This would be a temporary treatment measure and the NGT would be removed once she is well. When Mdm L recovers from hypoactive delirium, the team will engage her again to explore her wishes.

The medical team shared the above recommendations with Mdm L's family, and explained the reasons why they felt that inserting the NGT will be in Mdm L's best interests and not directly going against her wishes. Mdm L's family agreed with this and felt relieved.

The medical team and family both agreed that once Mdm L became more alert, they would try their best to elicit her preferences regarding the NGT from her.

Conclusion

Mdm L's story illustrates how it is critical to gather accurate and in-depth information in order for proper clinical and ethical analysis. The best interest principle can only be applied when there is genuine understanding of the patient's values, beliefs and preferences. The importance of communicating honestly and openly with family members to understand their views and concerns is also clearly demonstrated here.

Finally, it is important to remember that all clinical decisions are to be made with the patient and their families, and not for them. In order to obtain good patient outcomes, it is essential that the relationship between the doctor, patient and their family is built on open communication and trust.

Further readings

- Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of biomedical ethics: marking its fortieth anniversary. AM J Bioeth 2019; 19(11), 9-12.

- Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ. (2010). Clinical ethics: a practical approach to ethical decisions in clinical medicine. Linacre Quarterly, 50(2), 13.

- Lo B. Resolving ethical dilemmas: a guide for clinicians. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012.

- Rhodes R, Alfandre D. A systematic approach to clinical moral reasoning. Clinical Ethics 2007; 2(2), 66-70.

- Sulmasy DP, Sugarman J. The many methods of medical ethics (or, thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird). In: Methods in medical ethics. Washington DC, Georgetown University Press, 2001: 18.

- Veatch RM, Haddad A, Last EJ. Case studies in pharmacy ethics. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.