“Are you from the police?” I asked the man.

I was attending my first smoking cessation counselling session. I was 13. There were four other youths in the session. They all look slightly older than me, I thought.

The man looked shocked and seemed to be at a loss for words.

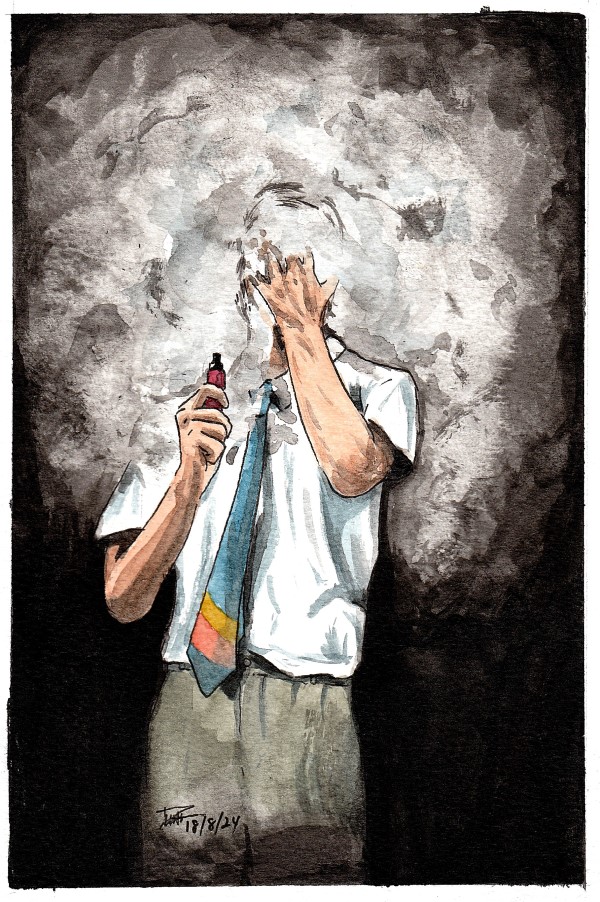

This is silly. I come from a good school – why am I here at this counselling session with these losers? I have already stopped smoking – it is so old fashioned. People have moved on to vaping. Wait, he is talking…

“I’m not from the police. I work with people who want to live a life of freedom without being reliant on a drug called nicotine, which is found in cigarettes. You’re here because someone wants you to quit smoking. But that’s their goal. What’s your goal?”

I heard what he said, but I was lost in my thoughts. Smoking? I no longer smoke – I vape. I have been vaping for a few months now. About half of my friends have switched to vaping. A few of us in school had found a good supplier – he was not the cheapest, but he was reliable and discreet. That stuff is so good; there is no smell that sticks to your clothes, it is easier to hide, and teachers cannot catch us. I do not have to beg adults to buy cigarettes for me anymore. It is much better than smoking. I was just unlucky that someone saw me vape and thought I was smoking, and reported me to the school. Do we have to declare it? Does he already know? Do I tell him? Will I get into more trouble if I declare that I vape?

“Anyone ever tried to stop smoking?” All our hands went up. It is true. We have all tried before. Some of us managed to stay away for a while, but we all came back to the habit. Man, it was difficult.

“So why did you come back to smoking?”

It is simple – the cravings. This intense desire to take another puff, even though I hear from school that it is bad for health. It is almost like my life depends on it now.

I cannot help it. In fact, I hate it.

It has been about three weeks now. My guy could not get a resupply of vapes. “Trouble at the customs,” he said. So much for reliability. It has been tough, these cravings are unbearable. Sometimes I just want to punch the wall as hard as I can. Of course, I do not really want to punch the wall. I just want to feel some pain so that I can distract myself from these cravings.

Who knows when this suffering will end? Actually, I could end it all right now instead of suffering through the intense craving. Just one more puff, that would do. Should I?

It is tough coping with the withdrawal symptoms. I cannot think properly, I cannot exercise properly. I have been shouting at my mum so much this week because I get irritated by the smallest thing… this is so unlike me.

“There are many ways that people manage their withdrawal symptoms. Even nicotine patches might be an option, but it is different for everyone so if you’re serious about kicking the habit, you will have to be honest with me so I can help you.”

Honest? Can he really help me? He sounds like he knows what he is talking about. Should I trust him? Or perhaps… I could just contact Dylan later to check if he has a fresh supply of vapes coming in later this week.

Sigh… What should I do?

Encountering young people who vape

For healthcare professionals who attend to people who vape, our first duty of care is to the patient. But we also know that vaping is illegal, and we have our citizen’s responsibility to alert the authorities when a crime has been committed. And this decision is much more difficult when the person in front of you is only 13 years old, like in the preceding anecdote. You worry about his future, her future, their future. A whole series of questions might go through your mind. What are the authorities going to do with them? Will they be fined? Can they pay the fine, especially when their family circumstances are already difficult to start with? Will they go to jail if their parents cannot pay the fine? Will their parents go to jail?

These questions and worries distract us from our duty of care, sometimes to the extent of being extremely careful with how we document these encounters in our medical notes. What if I wrote that the patient is vaping, without reporting to the authorities? Will I be liable? Will I lose my license?

And so we may end up ignoring or under-treating it. We say to the patient, “Stop vaping, it’s illegal”, and hope for the best. Yet deep down, we know that this does not work most of the time. We are not surprised when we hear that the patient has been caught for vaping – it was inevitable. At least it was not me who reported him/her; I would not want that on my conscience. But I do still feel guilty – that I did not do enough for him/her. I knew he/she needed some form of counselling, cessation support, perhaps even nicotine replacement therapy. But what can I do for this patient, within the boundaries of the legal system?

Imagine if we had an amnesty programme for youths who vape.1

What the youths really need

Firstly, we have to acknowledge that youths are a vulnerable group – which is also why there are many things that they are unable to do legally until they reach 18 (eg, driving, drinking) or 21 (eg, voting, smoking) years of age. But the tobacco industry comes up with a product that targets and appeals to youths – electronic cigarettes/vapes. This is not a fair fight – our youths do not stand a chance, even more so if they come from vulnerable social circumstances. As a society, we need to protect them. And if they fall prey to the unscrupulous marketing tactics by these device manufacturers, we need to help them, not add to their suffering.

Secondly, kindness and mercy are not enough, and neither is simply not punishing them. It is extremely difficult to crawl out of this hole of vaping addiction without external help. These youths are facing many other life challenges – peer pressure, schoolwork, puberty, family relations, etc. With so many stressors, it is easy to lapse and fall back into the habit of smoking or vaping as a form of escape. The amnesty programme is thus not simply “not punishing” – that would be a missed opportunity. The programme should start off by identifying youths who vape, before moving on to providing professional help. This can include social support in the school and home environment, and access to professional services such as counselling, psychological support and medical treatment.

Lastly, such a programme is not without precedence. The Singapore Armed Forces Amnesty Scheme was introduced in 1976 to provide an opportunity for drug abusers to seek help. Under the scheme, drug offenders who confess the first time will not be punished.2 Importantly, they will also receive counselling and rehabilitation support to help them kick their habit.

Call to action

Our nation’s birth rates are falling and our youths are a precious resource. Let us be steadfast and put in place this amnesty scheme for young people who vape. Let us not put healthcare professionals in such a sticky ethical dilemma, but let them focus on doing the right thing. Let us help parents, families, counsellors and teachers by making it easy for them to help these youths. Let us help the youths, who might have stumbled into this situation for various reasons, to get out of this habit and be able to access the help that they need.

Illustration by Dr Puah Ser Hon