Mental health challenges among children and adolescents in Singapore have been increasing, mirroring global trends. The Singapore Youth Epidemiology and Resilience study conducted by the Yeo Boon Khim Mind Science Centre found that one in three youths aged ten to 18 years old experience symptoms such as anxiety and depression.1 Academic pressure, social media and shifting family dynamics contribute to this rise, making early detection and intervention crucial.2

While the medical model is essential for diagnosing and treating mental health conditions, there is growing recognition of the need for a more integrated approach. Expanding beyond medical interventions to include social factors – such as family, school dynamics and community influences – can enhance the recovery and resilience of young people.

Expanding beyond the medical model

While the medical model is essential, it often focuses too heavily on symptoms, leading to over-medicalisation.3 Over- reliance on medication or psychotherapy without considering the social and environmental factors that contribute to these issues can result in incomplete care.

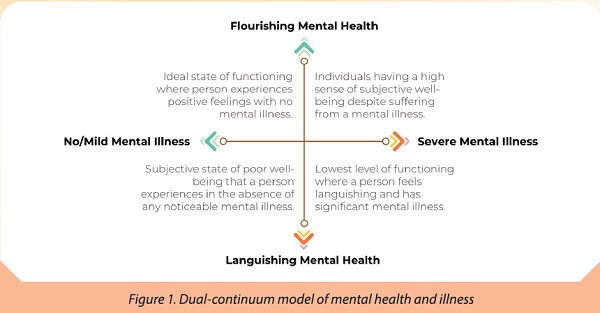

The dual continuum model provides a more nuanced view, showing that mental health and mental illness exist on separate spectrums. A person can have good mental health even with a diagnosed condition, or poor mental health without a formal diagnosis.4 This framework encourages early intervention, focusing on emerging signs of distress, which prevents waiting for conditions to worsen.

The clinical staging model complements this by offering a structure for early intervention based on where individuals fall along a continuum of illness.5 The stages start with an at-risk but asymptomatic state (stage 0), with increasing severity to nonspecific symptoms or an attenuated syndrome (stage 1), full-threshold disorder (stage 2), recurrence and persistence of illness (stage 3), and end with severe, unremitting illness (stage 4). By recognising early signs and addressing broader social factors, treatment can be more tailored to individual needs, preventing further escalation.

Therefore, a more integrated care model that balances medical treatment with social interventions is especially important for youths. Youth mental health is deeply connected to their environment, and a holistic approach ensures comprehensive support, addressing the root causes of distress rather than just managing symptoms.

Understanding mental health challenges

Mental health issues manifest differently in children and adolescents, making early intervention essential. Younger children often lack the vocabulary to express their emotions, resulting in behavioural changes such as irritability or withdrawal. Psychosomatic symptoms, like headaches and stomach aches, may mask deeper emotional distress.

In contrast, adolescents may show mood swings, social withdrawal and risk-taking behaviour. Academic stress, peer relationships and social media often exacerbate these challenges. By recognising these developmental differences, healthcare professionals can tailor their approach to ensure children and adolescents receive the appropriate care.

Despite the increased awareness of mental health, many youths avoid seeking help. In a 2023 evaluation of Singapore Children's Society (SCS) youth centres, common reasons for not seeking help include desire for independence, privacy concerns, fear of burdening others and a lack of trust. Some youths may not even recognise their mental health challenges and believe they should manage them alone.

Furthermore, parents may unintentionally delay help-seeking by misinter¬preting psychosomatic symptoms as physical issues or dismissing the youths' concerns as "just a phase." Tinkle Friend, the only national children helpline and chat service, provided by SCS, found that children often felt discouraged by dismissive attitudes from adults. One child shared, "[My mum] said that in the olden days, no one helped her, and that I was very weak to ask for help." Another child remarked, "because they'll say 'aiyo, don't be crazy lah, therapy is for those emotionally hurt people.'" These statements show how stigma reinforces the reluctance to seek support.

Healthcare professionals can break down these barriers by normalising mental health discussions during routine check-ups.6 Open-ended and persistent questions like "Is there anything that's been worrying you lately?" and "What else?" can foster meaningful conversations. Educating families about the connection between mental and physical health also helps them to understand that emotional distress can often manifest as physical symptoms. This insight would reduce stigma and empower parents to seek help for their children early.

Integrating medical and social lenses for comprehensive care

To fully support youth mental health, it is important to integrate medical and social lenses in their care. Family dynamics, school environment, peer relationships and community influences all play a role in shaping a young person's mental health.

One practical way of integration is the use of mental health screening tools. As recommended by Goh et al,2 these tools can be administered in waiting areas before consultations to help identify mental health concerns early and open up discussions addressing medical and social factors with the child and their family.

Collaboration with social services, schools and community resources is equally important. For example, a child facing bullying and school avoidance may benefit from interventions beyond medical treatment, such as a warm referral to school counsellors to create a safer environment. Similarly, linking families to social services that provide financial or emotional support can alleviate stressors that exacerbate mental health problems.

Advocating for recovery-oriented care

The focus of recovery-oriented care goes beyond symptom reduction. It helps children and adolescents build resilience, develop coping skills and achieve long- term well-being. A key aspect of this approach involves recognising that recovery is a deeply personal and non-linear process that involves changes in attitudes, values and goals.7 Youths need care that supports their ability to live meaningful lives, even while managing their mental health conditions.

For healthcare professionals, this means going beyond symptom management to address underlying factors contributing to distress. A child struggling with anxiety due to academic pressure may benefit from therapy, combined with practical strategies such as stress management or time management skills. These tools equip young people with lifelong skills to manage future stressors.

Engaging youths in their own care is also key to promoting recovery. According to the CHIME framework,6 key processes in recovery include connectedness, hope and optimism about the future, identity, meaning in life, and empowerment. Involving youths in treatment decisions fosters ownership of their recovery process, leading to improved outcomes.

By focusing on resilience and personal growth, recovery-oriented care empowers youths to live more fulfilling lives. This holistic approach aligns with broader efforts to integrate medical and social lenses, ensuring that young people are supported emotionally, socially and mentally.

Flourishing Minds: a community resource for doctors

One of the ways healthcare professionals can enable comprehensive, recovery- oriented care is by partnering community- based mental health services such as Flourishing Minds (FM), provided by SCS. The services provided include the development of mental health literacy, early intervention for emerging issues and therapy for diagnosed conditions.

A vital part of FM is the Oasis for Minds programme which offers early intervention and support for children and youths at risk or experiencing mild to moderate symptoms of mental health issues. The aim of the programme is to equip them with coping skills that build resilience and prevent the escalation of mental health concerns, and develop children, youth and parents' mental health literacy.

As an example, one of our clients, a 17-year-old girl, suffers from severe eczema since young. This resulted in sleep disruption, social withdrawal and eventually developed into social anxiety. If she were referred for appropriate interventions alongside her medical care early on, she could have learnt strategies to better manage her anxiety, which would have likely boosted her self-esteem to better engage in school and social life, thereby preventing the diagnosis of social anxiety. Her family would likely also have been better equipped to provide her emotional support.

With such partnerships in the community, doctors can ensure that their patients receive holistic and comprehensive care that bridges medical treatment with psychosocial intervention and broader social support. As a strong network of support, we can foster long-term well-being for the younger generation.