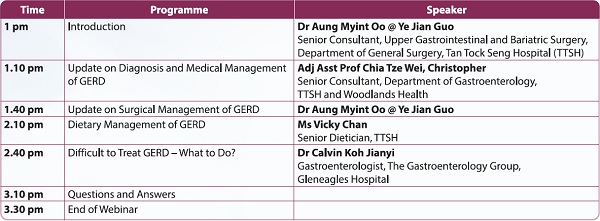

In line with the 24th Annual Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Awareness Week from 19 November to 25 November 2023, SMA organised a webinar on 18 November titled "Updates on GERD: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease" for clinicians and primary healthcare professionals, supported by AstraZeneca. A total of 37 clinicians attended the webinar.

Presented in this article is some general information on GERD and its management for fellow colleagues' reference.

Understanding GERD

GERD is a condition where the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications.1

GERD can be classified into three different phenotypes based on the endoscopy and histopathology findings: (a) non-erosive reflux disease (NERD), (b) erosive esophagitis (EE), and (c) Barrett's esophagus (BE).2 NERD is the most common type of GERD, followed by EE and BE.

The multi-factorial pathophysiology of GERD can be best explained by the following mechanisms:3

- Impaired lower esophageal sphincter function and transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESR);

- Presence of a hiatal hernia;

- Impaired esophageal mucosal defence against the gastric refluxate; and

-

Defective esophageal peristalsis.

In 2005, the prevalence of GERD in the Western part of the world was around 10% to 20% while only less than 5% was reported in Asia.4 However, with the increase in the prevalence of obesity across Asia, the GERD incidence rate is rising in Asian countries, including Singapore, as reported by Lim et al in 2005.5

Risk factors include obesity, hiatal hernias, smoking, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ageing, irritable bowel syndrome, and anxiety/depression, among others.3

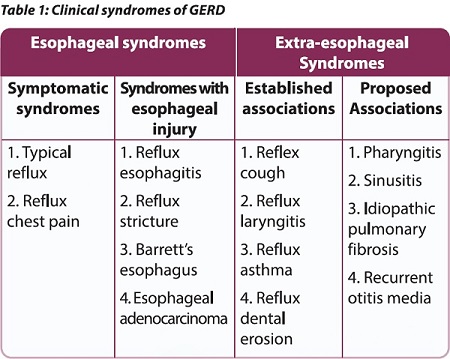

Clinical syndromes can be either esophageal or extra-esophageal (see Table 1).1

Clinical evaluation and diagnosis

Though upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy is not required to diagnose GERD, it can detect esophageal manifestations such as malignancy, Barrett's metaplasia and EE (severity graded using the LA classification system from A to D, with D being most severe). Upper GI endoscopy can also rule out other aetiologies in patients who are refractory to proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs).6

Esophageal manometry can help diagnose esophageal motility disorder and is useful in ensuring the ambulatory pH probes are in the correct position. It is also useful in evaluating the peristalsis function of the esophagus before anti-reflux surgery.6

Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring can help confirm the diagnosis of GERD. The monitoring device can be wired (a trans-nasally placed catheter) or wireless (a capsule-shaped device affixed to the distal esophageal mucosa). Alternatively, pH impedance monitoring can be used; it is able to detect weakly acidic reflux in addition to acid reflux, and is more useful in detecting symptom-reflux correlation.6

Management of GERD

Lifestyle modification

Weight management, avoiding late meals (within three hours of bedtime), raising the head of the bed by six to eight inches, stress reduction, avoiding trigger foods (eg, caffeine, chocolate, spicy foods), smoking cessation, and avoiding tight-fitting clothing may help with GERD symptom relief.7 Apart from the first three listed, the evidence supporting the symptom relief efficacy of other lifestyle modifications is weak.

Pharmacotherapy?

Antacids are more effective than placebos in relieving heartburn symptoms within five minutes, but provide relief for only 30 to 60 minutes. Antacids neither prevent GERD nor heal esophagitis.

Surface agents such as Sucralfate also have a short duration of action and limited efficacy, and their use is limited to managing GERD in pregnancy.8

Compared to antacids, histamine H2-receptor agonists have slower onset but longer duration of action, lasting four to ten hours. Though effective in patients with mild and intermittent symptoms, their efficacy is limited in EE and ineffective in severe esophagitis.

PPIs provide faster and more effective symptom relief, as well as healing of EE. Patients with EE or BE require maintenance acid suppression with standard PPI doses. For patients without EE or BE, PPIs should be prescribed at the lowest dose for the shortest duration appropriate to the condition. A step-up approach increasing the therapy's potency can be considered in patients with recurrent symptoms, using repeated eight-week courses of acid suppressive therapy. Specialist referral can be considered if patients do not respond to one daily PPI dose (ie, refractory GERD) or cannot tolerate or are not willing to take PPIs in the long term.8

Additive therapy with neuromodulators for TLESR; eg, low doses of baclofen (5 mg to 10 mg twice a day before meals) may be helpful for patients with refractory or non-acid reflux GERD. The dosage can be incrementally increased while monitoring the side effects in patients who are not responding to treatment.9

Endoscopic and surgical treatments

Anti-reflux procedures are usually indicated for patients who are refractory to medical therapy, but not recommended in patients who have a complete lack of response to PPI therapy.

Available endoscopic anti-reflux procedures include:10,11

Available anti-reflux surgical procedures include:10,11

According to the 2022 American College of Gastroenterology practice guidelines,12 anti-reflux surgery performed by an experienced surgeon is recommended as an option for long-term treatment of patients with objective evidence of GERD, especially those with severe reflux esophagitis (LA grades C or D), large hiatal hernias, and/or persistent, troublesome GERD symptoms.

Finally, GERD patients with obesity who are willing to consider bariatric and metabolic surgery can undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass but not sleeve gastrectomy.11