Healthcare professionals in their routine work will come across vulnerable persons and those with diminished capacity as patients presenting with a medical problem, physical injury or psychological disorder, which could suggest neglect by caregivers, family violence, physical or psychological abuse and even self-neglect.

This article intends to inform healthcare professionals of the various statutes in Singapore created for the protection of vulnerable persons and persons with diminished capacity, and it discusses how the law impacts the relationship between the healthcare professional and the vulnerable person/patient.

Statutes relating to vulnerable persons

In their motivation and actions to help these patients, it is useful for healthcare professionals to be aware of the laws or statutes relevant to this area. Here, we outline the important statutes as they were developed and list them in chronological order.

- The Women's Charter 1961 – focused on the protection of family members and children against family violence.

- Children and Young Persons Act 1993 (CYPA) – to provide for the welfare, care, protection and rehabilitation of children and young persons who are in need of such care, protection or rehabilitation.

- Maintenance of Parents Act 1995 – to make provision for the maintenance of parents by their children, for those unable to maintain himself or herself adequately.

- Mental Health (Care and Treatment) Act 2008 – to provide for the admission, detention, care and treatment of mentally disordered persons who pose a danger to themselves or others.

- Mental Capacity Act 2008 (MCA) – came into force in 2010 to protect people who may lack mental capacity and to allow those with capacity to appoint someone they can trust to make decisions on their behalf in the event that they lose their capacity.

- Protection of Harassment Act 2014 – to protect persons against harassment and unlawful stalking and false statements of fact.

-

Vulnerable Adults Act 2018 (VAA) – to make provision for the safeguarding of vulnerable adults from abuse, neglect or self-neglect.

How statutes impact the clinician-vulnerable person professional relationship

Healthcare providers at all levels of the healthcare system will encounter patients with diminished mental capacity. The reason for the diminished mental capacity may be due to various reasons (eg, children not having acquired the mental capacity yet, people with intellectual disability who lack mental capacity, or adults who lost their mental capacity due to various impairments to their mind or brain, such as due to head injury or dementia).

It is important to remember that mental capacity is decision specific and time sensitive. In all settings, it is important that the clinician assesses if the patient has the mental capacity to make the particular clinical decision at the point in time.

Children

The CYPA defines a "child" as someone who is below 14 years of age, and a "young person" as someone who is aged 14 years and above, but below 18 years old.1 This legislation provides for the welfare, care, protection and rehabilitation of children and young persons who are in need of such care, protection or rehabilitation and to regulate homes for children and young persons. It is worth noting the overarching principles of this Act which states that:

- the parents or guardian of a child or young person are primarily responsible for the care and welfare of the child or young person, and they should discharge their responsibilities to promote the welfare of the child or young person; and

-

in all matters relating to the administration or application of this Act, the welfare and best interests of the child or young person must be the first and paramount consideration.

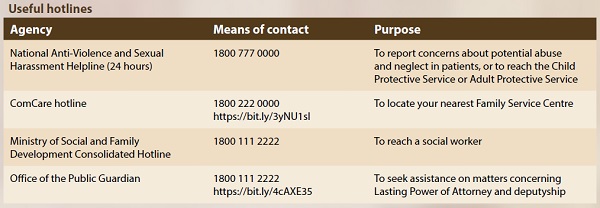

In the clinical setting, when there are issues relating to the safety or well-being of a child or young person, the CYPA may be relied upon to provide for those aspects of care and protection of the child or young person. In a secondary healthcare setting such as a restructured hospital, there would be medical social workers (MSWs) who can work with the parents and caregivers of the children and if necessary, they can raise their concerns to the Child Protective Services (CPS) under the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF). CPS investigates cases involving serious abuse or neglect of children and young persons in accordance with the statutory framework set out under the CYPA. The threshold for CPS to exercise various powers under the Act is predicated on whether there are reasonable grounds to believe that a child or young person is in need of care or protection. In the primary care setting, where there may not be social workers working with them, GPs and other healthcare professionals who have concerns for the children they encounter may report their concerns to the National Anti-Violence and Sexual Harassment (NAVH) at 1800 777 0000. They may also refer them to the neighbourhood Family Services Centres (FSCs). To find the FSC in your neighbourhood, you can call the ComCare hotline at 1800 222 0000 or visit https://bit.ly/3yNU1sI. To call a social worker in the community in Singapore, use the MSF Consolidated Hotline at 1800 111 2222.

Adults lacking mental capacity

In the clinical management of adult patients who are aged 21 and above, it is important that the clinician in charge of their care determines their mental capacity to make decisions for their clinical care. The MCA and the accompanying Code of Practice provides the relevant legislative framework and guidance for this.2,3 For someone to lack mental capacity for the decision at the material time, he/she must first have an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain and as a result of that impairment is unable to (i) understand information about the decision; (ii) remember that information; (iii) use that information to make a decision; or (iv) communicate their decision by talking, using sign language or any other means. If the patient has mental capacity, their autonomy has to be respected and they can make decisions about their own care and treatment.

The MCA also provides for the creation of a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA). The LPA is a power of attorney under which the donor confers on the donee (or donees) authority to make decisions about all or any of the person's personal welfare and/or property and affairs when the person no longer has capacity to make such decisions. Healthcare professionals are expected to work closely and collaboratively with the person(s) holding the LPA of the person with diminished capacity.

If the patient lacks mental capacity for the decision at hand, then the clinician needs to act in their best interests. While "best interest" is not defined, the MCA sets out the steps to be followed when making decisions in the best interests of the patient. It is important that the clinician considers whether it is likely that the patient may regain capacity to make the decision and if so, the decision may be delayed unless in an emergency. The clinician must also consider the patient's past and present wishes and feelings, and any beliefs and values that may influence the decision if the patient had capacity. Wherever possible, the clinician should consult with and hear the views of the donee(s) of the LPA and those who have an interest in the welfare of the patient, which may include members of the clinical team, professionals outside the clinical team involved in the care of the patient, and the patient's family and friends. The clinician as the decision-maker has to weigh up all relevant factors to determine the best interests of the patient and act accordingly thereafter.

Healthcare professionals may at times have concerns as to whether the LPA has been revoked, or face situations where the donee(s) may not be acting in the best interest of the donor, or where there are persistent and serious disputes between the donee(s) and family members. In such situations, healthcare professionals can seek help and advice from the Office of the Public Guardian at their website (https://bit.ly/4cAXE35.) or call the MSF Consolidated Hotline.

Vulnerable adults

Regardless of the mental capacity status of the patient, if the patient who is aged 18 years or older falls within the definition of a vulnerable adult, then the VAA may be relevant in the management of the patient. A vulnerable adult is defined under the Act as an individual who, because of mental or physical infirmity, disability or incapacity, is incapable of protecting himself or herself from abuse, neglect or self-neglect.4

In a secondary healthcare setting such as a restructured hospital, the clinician can refer to their hospital's MSWs, who are often also part of the clinical team, and they can work with the patient's family and community agencies to provide the social care and support that the patient requires. However, on occasions where these interventions are inadequate, state interventions may be necessary as a last resort. MSWs can refer these cases to the Adult Protective Service (APS) under MSF who can exercise powers under the VAA to protect vulnerable patients from abuse, neglect or self- neglect. In the primary care setting, GPs or other clinicians who may have concerns for their patients may call the 24-hour NAVH Helpline to reach the APS to raise their concerns or refer them to the neighbourhood FSCs which are empowered to assess and make the necessary referrals. FSCs provide support for low-income and/ or vulnerable individuals and families with social and emotional issues, and work towards stability, self-reliance and social mobility.

The Director-General of Social Welfare or a Protector, who is a senior officer from the APS appointed by the Director, can enter private premises to assess a suspected vulnerable adult if there is reason to believe that a vulnerable adult is at risk of or has been subjected to abuse, neglect or self-neglect. If required for the vulnerable adult's safety, he/she can be removed and committed to a place of temporary care and protection or to the care of a fit person. The Director or Protector can apply for Court orders for further committal of the vulnerable adult and other orders to safeguard his/her well-being, including orders to ensure that he/she receives the necessary medical treatment, that his/her residence is made safe for habitation, to restrict who may have access to the vulnerable adult, etc. As part of the process, the APS will need to know if the vulnerable adult has mental capacity for some of those decisions being taken, and clinicians, especially psychiatrists, who are mental capacity assessors appointed by the Director- General of Social Welfare under the VAA may be required to undertake mental capacity assessments on the vulnerable adult and produce a mental capacity assessment report using Form 64A (https://bit.ly/3AuRHaq) to the APS.

Conclusion

Clinicians managing patients with diminished mental capacity or who are vulnerable should be familiar with the relevant statutes that apply to them so that they can work within those legal frameworks in providing the necessary medical care and treatment to their patients.