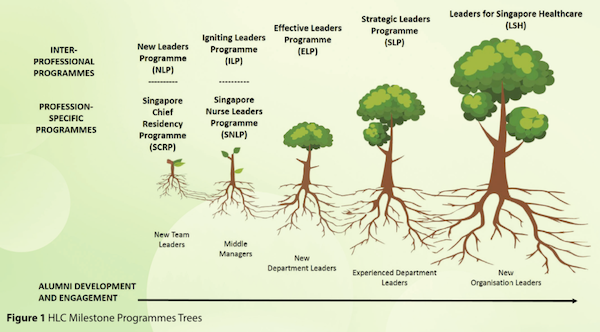

The symbol of the Healthcare Leadership College (HLC) is a tree. Good trees have solid roots; they have strong trunks with sturdy branches and healthy leaves, and they bear good fruit.1-3 Trees maintain a deep bond with each and every one of us, no matter the country, conviction or culture. And this is exactly why the tree – from a sapling to a mighty giant – is emblematic of the HLC.

More than a decade ago, it was noted that healthcare in Singapore had been growing the wrong way. The focus had shifted from treating the patient to treating the disease. Altruism was withering, and this trend needed to be stemmed. Ms Yong Ying-I, the then-Permanent Secretary of Health, set up the HLC in 2012 to rejuvenate the true ideals of our mission, and to reinject humanism into our profession and healthcare in general.

Values

The very first mission of HLC was to re-establish the importance and visibility of values, which form the core and the roots of HLC. Core values are similar across all our public institutions.4-6 They are built around compassion. True compassion is altruistic; it demands excellence and is expressed through service. Any organisation that holds to this for its own staff will display the same compassion for its patients.

Values define the organisation; just like the ten commandments were inscribed on stone for posterity, so too must values be made visible for all to see across time. The problem with values though, is that they must be held to even when it is hard. This requires an inner strength of conviction called moral courage. Moral courage is the primary enabler of our values; it is a sine qua non for leadership.

Moral courage

haps there is no better description of moral courage than that of General William Slim's (1891-1970).7 William Slim, described by Admiral Louis Mountbatten as the finest general World War II produced, said of moral courage: "You must have moral courage. Moral courage is a much rarer thing than physical courage. Moral courage means you do what you think is right without bothering very much what happens to you when you are doing it."8

This description is perfect for healthcare. Moral courage mandates that doing the right thing takes primacy over doing things right. There will be times when doing the right thing may come at some personal costs, and the choices will be made by an authentic leader's innate moral compass.

Sources of leadership wisdom

There is a paradox in healthcare. While failures of leadership have severe consequences for patients, the consequences for the leaders themselves are usually not direct, nor immediate.

In business, the consequences for leaders are direct. The business will go bankrupt and leaders will be replaced. In the military, the immediate consequences of failure are defeat and death for the soldiers, and often for the commanders.

I therefore think that it is the military leadership literature that is truly tried and tested, and the most valid. It can and should be applied to healthcare, and there is no better example than the COVID-19 pandemic. During these past two years, our intelligence was always changing, our plans always appeared to be less than perfect and upon execution of these plans, the reality looked very different.

One of the greatest military classics is the multi-volume treatise On War by Carl von Clausewitz (1780-1831),9 a Prussian general.10 He wrote these volumes after Prussia had been crushed by France in the Napoleonic wars. He says of plans, intelligence and reality: "Many intelligence reports in war are contradictory; even more are false, and most are uncertain", "The enemy of a good plan is the dream of a perfect plan", and "Everything takes a different shape when we pass from abstractions to reality."

Policies

If values are the roots of our tree, then the trunk is formed by sound healthcare policies. Strong national values and philosophies lead to good policies. They form the backbone of any healthcare system. If they are weak, the system will crumble.

I think that the central policy, that of accountability on the part of patients as well as the system, was established by Lee Kuan Yew. He stated in his memoirs that: "The ideal of free medical services collided against the reality of human behaviour, certainly in Singapore. My first lesson came from government clinics and hospitals. When doctors prescribed free antibiotics, patients took their tablets or capsules for two days, did not feel better, and threw away the balance. They then consulted private doctors, paid for their antibiotics, completed the course, and recovered. I decided to impose a charge of fifty cents for each attendance at outpatient dispensaries."11

Our COVID-19 response and policies were values-driven. The first duty of the government is to protect its people, and this is what Singapore has done. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong stated in 2020: "We will keep on doing our utmost to protect every Singaporean from COVID-19. Many people have been working tirelessly for the past two months. Our nurses and doctors, our contact tracers and healthcare staff. We thank them all for their efforts and sacrifices. Now we are all enlisted to join them on the frontline."12

He demonstrated the role of humanism in medicine when he promised to deliver healthcare to foreign workers in the country: "If any of their family members watch my video, let me say this to them: 'We appreciate the work and contributions of your sons, fathers, husbands in Singapore. We feel responsible for their well-being. We will do our best to take care of their health, livelihood and welfare here, and to let them go home, safe and sound, to you."'13

If we as a nation had not chosen this course of action for our migrant workers, there would have been damaging effects to our national character.

Execution

Policies have little use unless they are paired with well-articulated and well-executed strategies; these branch out from values-based core policy. Neither articulation nor execution is easy. They require a simplicity of intent, a clarity of logic and diligent determination. Stephen Bungay puts it very well:

"Having worked out what matters most now, pass the message on to others and give them responsibility for carrying out their part in the plan. Keep it simple. Don't tell people what to do and how to do it. Instead, be as clear as you can about your intentions. Say what you want people to achieve and, above all, tell them why. Then ask them to tell you what they are going to do as a result."14

Programmes at the HLC are designed on three interlacing principles:

- Thinking up – having a sound understanding of policy.

- Thinking across – across our institutions and the professions.

-

Thinking ahead – planning the future of healthcare delivery.

Three strategic manoeuvres were used in planning the future of healthcare in Singapore:

- Rationalising healthcare into three clusters – combining the dual juxtaposed strengths of consolidation and competition.

- Developing the "Three Beyonds" – Beyond Healthcare to Health; Beyond Hospital to Community; and Beyond Quality to Value.

-

A mindset recalibration from tribal-think to a systems-based approach of thinking for the good of the patient, the good of the healthcare system and the good of the nation.

We need to remember that there is no greater obstacle to successful execution than micromanagement.15

Outcomes

The fruits are the raison d'être of the HLC. These are the excellent men and women that HLC has trained: leaders that execute well-laid and well-conceived plans, based on values-driven policy, with the moral courage to do the right thing. The leaders we produce at HLC work for the good of all patients, their families, and both society and nation.16These leaders understand that the enemy may be the disease, but the ones that need the healthcare are the patient and the nation. After all, 下医医病, 中医医人, 上医医国 (the mediocre doctor treats the disease, the common doctor treats the patient, and the best doctor solves the problems of the country).