The medical school journey is filled with ups and downs. Clinical experiences often leave a lasting impression on medical students. This can be an inspiring clinician mentor, lessons in compassion or amusing anecdotes in day-to-day clinical interactions. We share the reflections of six medical students from their clinical postings and through these, give a glimpse on how these stories have shaped their training as student doctors.

Chen Xiaoyu

Earlier this year, I was allocated to complete my GP placement in a small town that rarely gets visitors from abroad. The daily schedule for medical students was simple – we take history and perform necessary examinations on the patient before calling in the GP, situated in another room due to COVID-19 restrictions, to review them.

Due to the busy schedule of our GP tutors who have to see their own list of patients, my colleague and I often found ourselves waiting in the consultation room with the patient for some time. In these cases, small talk often kicked in with some common topics, ranging from which year of medical school we were in to where we would like to work next. And of course, the most common question of them all being "Where are you from?"

While my colleague introduced his hometown in England, I prepared my rehearsed answer of being an international student from Singapore studying in the UK. Interestingly, people often expressed interest in our little red dot, with comments about the ban on chewing gum, our clean garden city, having strict laws, etc. And in some cases, "Oh, Singapore! Do you speak English there?"

Friends have told me that the Singaporean accent can be difficult for them to understand. This reminds me of the challenges that international students face in a foreign country. Not only are we studying there, we are also representing our country through our actions. For me, the Singaporean accent has been particularly heartwarming to hear, especially in an environment far from home. In my defence, I had similar challenges understanding the Scottish and Irish accents during my first few years in the UK, but I guess it is just part and parcel of living abroad.

Timothy Tay

The most memorable clinical experience occurred during my emergency medicine posting, where an elderly patient in cardiac arrest was brought into "resus" (resuscitation). With no time to waste, everyone immediately donned full personal protective equipment and got down to work. As it was my first "resus" case, everything seemed to be a blur. While I was still trying to process what was going on in the background, my supervisor suddenly grabbed me by the arm and instructed me to take over CPR. The next thing I knew, I was standing on a stool, hovering over the patient doing chest compressions, all the while hoping the patient would regain a pulse.

As time passed, the chest wall sunk deeper and deeper and the apparent chances of survival grew slimmer. Moments later, I was told to stop.

This was my first encounter with death. There and then, I didn't have time to fully digest what was going on and it took a while for the fact to sink in. Later, a doctor checked in on me to ensure I was alright, explaining that such situations can be overwhelming and I was free to reach out if I needed any help. With the fast pace of emergency medicine and the many patients to care for after, it can be easy to distance myself from this incident and quickly move on to the next bed. I found comfort in his words, for someone had acknowledged that it is understandable to feel for our patients who had passed under our care, and natural to sometimes feel overwhelmed.

This experience reminded me of how fragile life can be and that sometimes, despite our best efforts, not all lives can be saved. My takeaway is to always do my best for my patients, and although outcomes may sometimes be suboptimal, what matters is that I have given my all.

Nicholas Loh

During my family medicine rotation, I was posted to a GP clinic in Sengkang, which relishes a decent patient load. The clinic doctor possesses an excellent reputation, and it is not hard to see why. After sitting in for the first few consultations, I realised that he goes the extra mile to get patients personally involved in their care.

The GP keeps his handy physical copy of John Murtagh's Patient Education in the clinic. Towards the end of each session, with respect to patient education, he would flip to the relevant pages in the book and ask the patient to take a photo with their phone so that they can benefit from further post-consultation reading. The amount of time available for the doctor to provide personalised patient education is limited in the typical GP clinic. This is unlike the case in polyclinics, where there may be an advanced practice nurse who dispenses advice. As such, providing patient education via an esteemed book such as Patient Education is surely a reasonable alternative.

Moreover, this GP also has his own leaflets for patient education that he personally prepares beforehand to hand to the patients. He prepares these leaflets using Microsoft Word, and prints multiple copies to be kept in the clinics. These leaflets cover commonly encountered problems in the primary care setting (eg, fever in children, diarrhoea, constipation), and usually provide a short definition of the disease entity, common aetiologies, clinical features and appropriate patient advice. For example, in one such leaflet on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), I remember seeing a section advising patients to sleep in a left lateral decubitus position with their head elevated, and to avoid food and liquid consumption in the hours just preceding nocturnal slumber. Having a "Dos and Don'ts" section benefits patients because it advises them on practical steps they can take to manage their condition in partnership with their doctor. By extension, patients would feel that they play an important part in their recuperative journey, and this can have positive downstream effects on future patient adherence.

In sum, this particular doctor has left an indelible impact on me. Should I ever find myself in the realm of general practice in the future, the example set by this GP is certainly one that I would strive to emulate.

Alva Lim

"What does it mean to be compassionate? Why do we call them patients instead of clients or customers?" Dr Daniel Seng posed these questions to us – four clueless third-year medical students. Never before did we think about these words that we use daily. With Greek and Latin origins, the word patient originally means "one who suffers", and compassion, "to suffer with". Why did it matter to understand these words?

Entering the new clinical environment, we are taught to be empathetic and to show compassion to our patients. However these words, in the vast ocean of medicine, appear to have slowly lost their meaning. In our clinical years, we hope to learn as much as we can from each patient. When we examine patients, we aim to identify the clinical signs through physical examination that guide us to the final unifying diagnosis, allowing us to best manage the patient's condition. However, without the experience of seeing these conditions, we are at the mercy of the examiners. Fortunately, some conditions are commonly found; thus we scour the wards for such patients to practise our examination skills on.

Unfortunately, these patients, in their times of distress, would then be examined by countless medical students. On bad days, patients with excellent signs may be seen by medical students hourly, and not because the consultant wanted hourly check-ups on them. How could they possibly get any rest? Despite the lack of obligation, some medical students may push patients towards agreeing to be examined. "It will just take a short while", "Don't worry, it won't cause you any pain". Why should this convince patients and why are we not allowing the patients to refuse?

"Can you help me tell the other students not to come anymore?" "No, I cannot take any more medical students today." A great sadness, perhaps even disappointment, overcame me as I reassured the patients and thanked them for their time. Why do we leave patients feeling like this? When the patient is ill, they look towards the medical team for comfort, but when we forget to show compassion to the patients, we merely add on to their discomfort and suffering. I've seen patients turn from the loveliest and bubbliest people into the grumpiest individuals who shout at medical students before they even enter their wards. Who can blame them? When we approach patients with our intentions to learn, we may forget their own intentions. Beyond just fulfilling our intentions, we should give space for the patients to express their feelings and allow ourselves to share in their pain.

Let us suffer a little more with the ones who suffer.

Daniel Yap

The names and key identifying elements of this story have been modified to preserve patient confidentiality.

The setting to this story is one that might be recognised by a clinical medical student, albeit perhaps associated with a dash of sheepishness or guilt. A little bird whispers in our ear that there is a case to be clerked in bed 53, and we set off immediately to grace our new admission with our presence – our little entourage dressed in full purple.

At bed 53 lay Mr K, who seemed to be in rather good spirits despite his recent admission. He smiled at us and we gleefully smiled back, making the proper introductions and engaging in small talk, inquiring about him and his reason for admission.

Before we could get to the crux of the matter, the general surgery team stormed into the cubicle in their usual down-to-business fashion and approached us for fifteen minutes of his time. We erratically nodded our heads and scooted to the side, having been well trained in the cardinal rule of never standing in the way of a surgeon and his job.

The subsequent chain of events happened in a flash. Curtains were drawn, and the textbook SPIKES (Setting, Perception, Invitation, Knowledge, Empathy, Summary) approach to breaking bad news was applied in quintessential fashion. Colon cancer. Extensive metastases. Prognosis: six months, give or take. Chemotherapy to be started as soon as possible. The surgery team leaves.

We remained shell-shocked even after the curtains were drawn back. Mr K called to us to continue talking to him, as if nothing had transpired. As if no bullet had just been fired; as if it was simply a figment of our imaginations.

We composed ourselves and asked worryingly, apologetically if he was alright. He smiled, and mentioned that everything was okay. That the only thing he had on his mind was worry – not for himself, but for his mother. His mother had mild Alzheimer's, you see, and he was worried about how she would be taken care of after he passes. He was worried about how she would take his passing. He smiled and said that he was grateful for the few months he had left, to settle these issues and to find closure.

After ample time, we thanked him for sharing about both his medical condition and his mindset on the matter, and asked if there was anything at all that we could do for him before we left. Here came the pièce de résistance – his final answer and request:

"Just study hard for me, you all are our society's future. All our hopes rest in your hands."

Mr K's stoicism rang bright and clear that day and he showed us what it meant to him to be a carer for his mother, even as we acted as carers for him in the management of his cancer during his final days. He exemplified the importance of his - indeed, every patient's – personal priorities as a fundamental part of closure, as he stared into the face of looming death.

As we care for our patients, we remember that integrated care is multifold and immensely complex. And as we medical students learn from our mentors in the hospitals, from doctors and surgeons, we remember that sometimes our patients are the mentors who teach us the glimmers of information which reside closest to the heart. And finally, we are reminded that as we study, we study hard – not for mere examination purposes, but simply to be as best a doctor as we can be for our patients.

Who am I to deny this dying man's final request?

Wo Yu Jun

It's always the people that make for a memorable experience. A few months ago, I had the pleasure of an amusing encounter with a patient during one of my clinical postings as a medical student.

He strode into the clinic room with a nurse in tow, proclaiming loudly: "I AM HARD OF HEARING." The doctor nodded in reply and was promptly presented with a handheld device that looked somewhat like a mobile phone. "THIS IS A VOICE-TO-TEXT TRANSLATOR," the patient explained. "JUST PRESS THIS BUTTON, SPEAK INTO IT, AND SHOW ME THE TEXT ON THE SCREEN." Mildly perplexed, the doctor followed his instructions, and spoke into the device, "How are you?"

Before he had the chance to show the screen to the patient, the patient replied, "GOOD, THANK YOU." I was sure the doctor almost did a double take at that moment.

The patient's nonchalant answer, delivered with a casual shrug on the side, was: "I'M HARD OF HEARING, BUT I CAN STILL HEAR YOU."

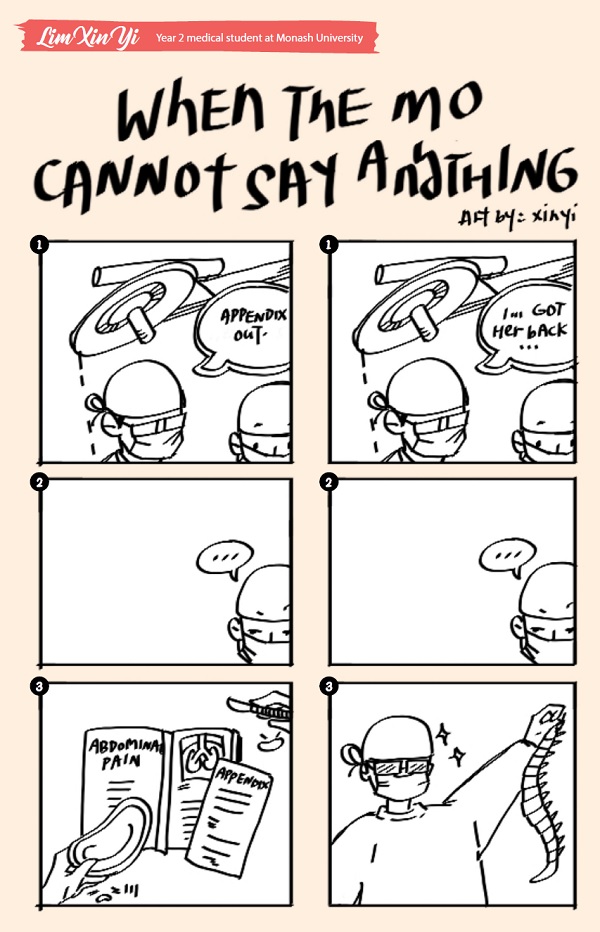

Lim Xin Yi