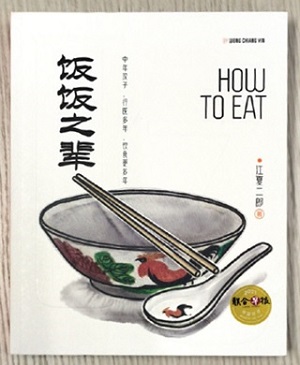

Most would be familiar with Dr Wong Chiang Yin, Council Member and Past President of SMA, and his many contributions to the medical profession. But did you know that aside from being a doctor, Dr Wong is also a wine connoisseur, a foodie and an author? SMA News speaks with Dr Wong to find out more about his relationship with food, how it led him to pen regular columns in Lianhe Zaobao, and about his recently published book How to Eat, which is now in its third print.

Growing up

Could you share with us a bit about your childhood and how it was like growing up?

My early years were spent in a two-bedroom Singapore Improvement Trust flat (precursor to the HDB flats) on Outram Hill, now demolished. Life was simple. My primary and secondary school years were then largely spent in a three-bedroom HDB flat in Holland Drive, now also demolished. I spent many hours playing at the void deck of the flat as well as around Holland Village. I was a Holland Village kid, version 1.0. In secondary four, we moved into a HDB executive maisonette and life got much better. Finally I had my own room, and I could bathe under a shower and did not have to squat in the toilet, not to mention that we had air-conditioning in the bedrooms as well. I felt like I was on top of the world then.

What is your fondest childhood memory of eating?

I grew up near Tiong Bahru Market, and the food sold there was great. The old market used to be housed under a zinc roof. I remember walking there with my family for meals, from our place on Outram Hill to the market. Some of my favourite stalls included the prawn noodles – now closed; the Teochew crystal dumplings (otherwise known as chwee jia bao) – now moved to Alexandra Hawker Centre; and the spare parts soup (Koh Brother Pig's Organ Soup) and lor mee – both still operating at the market.

What was your favourite dish growing up? Was there a dish you didn't like as a child, but eventually grew to love?

Wanton noodles and fish head noodles were my favourites. I am a Cantonese kid at heart. As for what I disliked, it was not so much a dish, but the papaya fruit because of its mushy texture. Serving in National Service (NS) has taught me to like it, because many meals in NS included papayas.

How to Eat – the column and the book

You shared in your book's foreword that you published your first column in 2016, with a total of 42 columns. Which of these would you say was your most memorable entry and why?

I like my first column about "kick school food" the best. I am a fan of Wong Fei-hung movies, from the black and white ones to the later ones starring Jet Li. I think this first column set the tone for future columns - a meal is a contest of one's understanding of food and cooking, between the person preparing and the person eating the dish.

How did you choose which dish to feature in your columns?

Any dish that I knew enough about to write approximately 1,000 Chinese characters for my monthly column in Lianhe Zaobao, or 2,000 characters (split over two months) could be considered. I gave preference to dishes and food that were commonly eaten and hence familiar to a wide audience. There is no point writing frequently about esoteric dishes that most people locally have not heard about, let alone eaten.

What served as your motivation and inspiration as you penned the monthly column in Lianhe Zaobao?

A commitment I made to my friend Anthony Tan, then-Deputy CEO of Singapore Press Holdings who first encouraged me to write the monthly column, was what kept me going. It was also to show that an Anglo-Chinese School (ACS) boy could write a column in Chinese. When the column first came out, a few of my ACS friends even thought that I had initially written it in English and asked me, "Who translated it into Chinese for you?"

When writing the column and sharing the culinary culture and origins of the dishes and ingredients, how did you go about your research?

First, I must already know something about the dish. The information I have came from what my late Cantonese grandparents and father told me over the years, as well as my conversations with chefs and restauranteurs. I don't start from scratch. Using this as a base, I may do research to beef up the content a bit. Of course, with the Internet, Baidu and Google, research is not difficult.

Would you say that you have covered the majority of the Cantonese and Nanyang dishes in your book?

There are still many other dishes in the Cantonese and Nanyang cuisine that I have not covered – roast duck, chicken rice, laksa, nasi lemak... so many more!

How long did it take you to translate and put together the book, How to Eat? Were there any challenges or difficulties in the process?

It took me about two months in all, during the 2020 circuit breaker. The more difficult part was actually writing the columns in Chinese from 2016 to 2019. Translating them into English came quite easily to me.

Relationship with food

When would you say you first got interested in food and its origins?

I think I am a naturally curious person. I remember many things my grandparents said to me about how food tasted in Guangdong province, where they came from. So when I first went to Hong Kong as a teenager, and later Guangzhou as a medical student, and ate the food there, I finally understood where they were coming from. And that was how it got me thinking about why some food are cooked and tasted the way they do.

Who would you say had the greatest influence in your pursuit of good food?

Probably my father and paternal grandmother (who hailed from Nanhai, Foshan, Guangdong). At the core, I have a Cantonese palate, the rest came later. Foshan is a place known for foodies and good food. I think my palate was honed from young from eating all the Cantonese food (prepared with ingredients from tropical Singapore). The Cantonese want their food fresh and the cooking needs to highlight the original flavours of the ingredients. It is beautiful food with "light make-up", unlike what you see sometimes nowadays, with folks trying to make food ingredients taste and look beautiful with "heavy make-up" methods.

What was the greatest distance (or effort) you have put in to obtain a dish?

Something I ate overseas which is unmentionable in this publication. Enough said.

Are you also a chef aside from being a foodie? If so, which dish would you say is your specialty?

I can cook, but do not usually have the time to. I would not say that I have specialties but dishes that I can cook include a classic Cantonese Lunar New Year dish – braised dried oyster, fatt choy (black hair moss) and Chinese mushrooms. I also do a decent miso cod, chicken cooked with red rice wine dregs (a Hakka or Fuzhou dish) and Toman (ie, snakehead) fish soup.

What is one local dish that you would always recommend to a foreigner/ friend?

I think the two most Singaporean dishes would be bak chor mee and Toman fish head bee hoon soup. These two dishes are not found commonly elsewhere, not even in Malaysia.

If you could only choose one dish to have for the rest of your life, what would it be?

Eating is about variety and choice, so no one dish fits the bill.

Is there any particular dish you love that can no longer be found in Singapore?

The chicken intestines that were sold at chicken rice stalls.

How to Eat is a bilingual book compiled from a gastronomy column in Lianhe Zaobao, written and translated into English by Dr Wong Chiang Yin. It made it into the Lianhe Zaobao 2021 "10 Good Books" List and is now in its third print. To know more about the book, read our Editor's review of it at https://bit.ly/5306-Review.

All profits from the book go to the SMA Charity Fund (SMACF) which supports living expenses of medical students in need.

To find out more about SMACF, visit https://bit.ly/aboutSMACF or scan the code above.

To find out more about SMACF, visit https://bit.ly/aboutSMACF or scan the code above.