The Singapore Parliament passed the Medical Registration (Amendment) Bill 2020 on 6 October 2020, and the

amendments will come into effect imminently. The amendments largely relate to the reform of the Singapore Medical Council’s (SMC) disciplinary process, which came close on the heels of the highly publicised cases of Dr Lim Lian Arn and Dr Soo Shuenn Chiang in 2019. Following the medical profession’s strong reactions to these cases, the Ministry of Health (MOH) established the Workgroup to Review the Taking of Informed Consent and the SMC Disciplinary Process. Co-chaired by a Senior Counsel, the Workgroup conducted several town halls with stakeholders of the healthcare sector. Its recommendations, accepted by MOH on 3 December 2019,1 found their way into the amended Medical Registration Act (MRA).

The legislative amendments aim to:

- Reduce delays and facilitate more expeditious resolution of complaints;

- Improve the quality and consistency of processes and outcomes;

- Protect patients more effectively; and

-

Encourage the amicable resolution of complaints and facilitate a less adversarial disciplinary process.2,3

For the purposes of this article, the pre-amendment law will be referred to as the “old MRA”4 and the post-amendment law will be referred to as the “new MRA”.5

Reducing delays and expediting complaint resolution

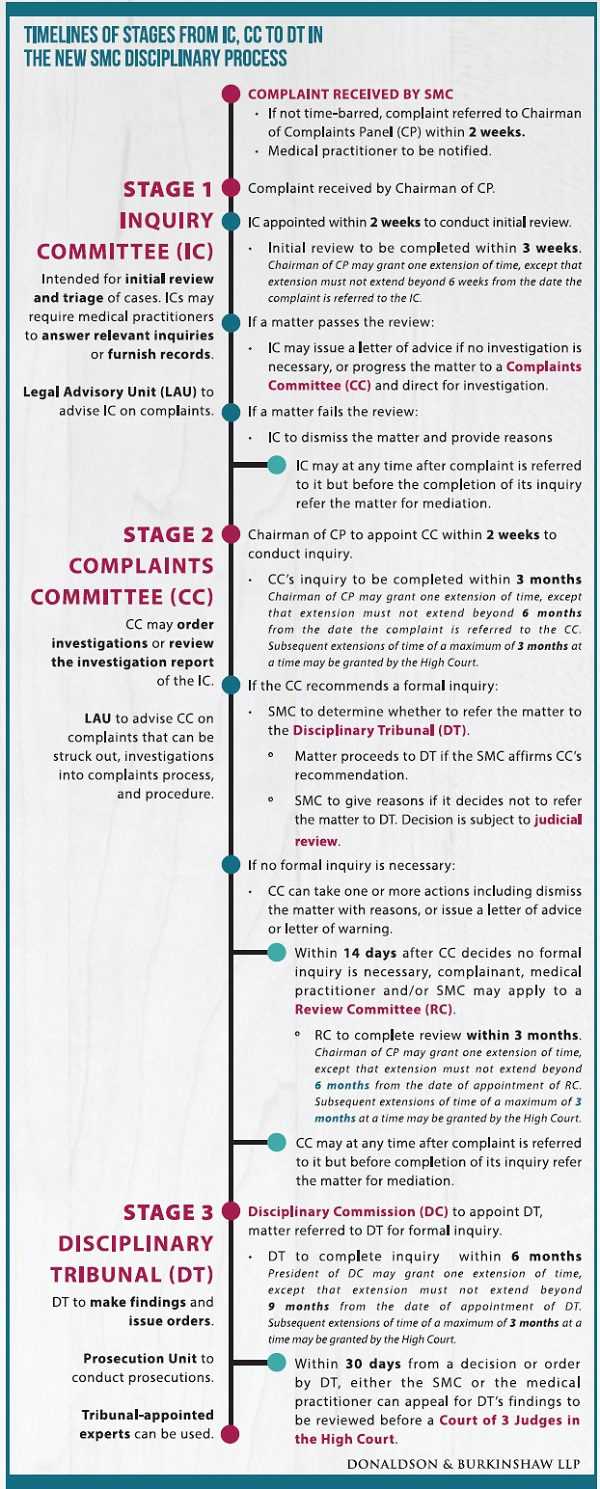

To facilitate the expeditious resolution of complaints and reduce delay in the disciplinary process, some key amendments in the new MRA are as discussed below.

Introduction of a limitation period

Under the old MRA, there is no limitation period for lodging a complaint. This means that a complaint can be lodged several years after the incident that gave rise to it and still be processed by the SMC. This is unsatisfactory as the elapsing of time can negatively impact witness memory and the retention of relevant documentary records.

A limitation period for complaints is introduced under the new MRA such that the SMC must not refer to the Chairman of the Complaints Panel (CP) or the President of the Disciplinary Commission (DC) any complaint that is made after the expiration of:

- Six years after the date of the act, conduct or occurrence in question; or

-

Six years after the earliest date the complainant/SMC (as the case may be) had knowledge of the act, conduct or occurrence, or could with reasonable diligence have discovered it.

This is subject to a public interest exception where, if the President of the DC opines that it is in the public interest for a time-barred complaint to proceed, the complaint will be referred to the Chairman of the CP within two weeks, for the appointment of a Complaints Committee (CC).

Faster notification of complaints to medical practitioners

Under the old MRA, a medical practitioner is only notified of a complaint after the three-person CC has been constituted by the Chairman of the CP, if investigation is directed and that the medical practitioner has a case to explain. The CP from which members of the CCs and Disciplinary Tribunals (DTs) are drawn comprises council members, other medical practitioners and laypersons.

Under the new MRA, the medical practitioner will be notified when a complaint made against them is referred to the Chairman of the CP or directly to the President of the DC, as the case may be. This is intended to allow medical practitioners to respond more quickly to complaints.

Upfront submission of relevant documents and information

One feedback to the Workgroup was that the piecemeal nature in which documents and information are submitted often lead to delays in SMC investigations under the old disciplinary process.6

Under the new MRA, the complainant at the time of submitting a complaint will have to provide all relevant documents and information in their possession. Likewise, any written explanation by the medical practitioner will have to be accompanied by every relevant document and information in their possession.

Introduction of Inquiry Committees to sieve out unmeritorious complaints

Under the old MRA, there is a two-stage process involving the CC and the DT, whereby a DT is constituted if the CC is of the view that a formal inquiry is warranted. From the Workgroup’s review, it was found that a significant percentage of complaints were ultimately without merit, with some dismissed for being frivolous or vexatious and 50% of complaints were dismissed at the CC stage after investigation.6 Each such complaint took up considerable resources to manage.2

The new MRA will establish Inquiry Committees (ICs) to serve as an upfront mechanism to filter and dismiss complaints that are frivolous, vexatious, misconceived or lacking in substance. The IC comprises a chairman and one other member, both registered medical practitioners. The IC must complete its inquiry within three weeks and decide whether to dismiss the complaint, issue a letter of advice, or refer the matter to a CC for further investigation. The Chairman of the CP may grant one extension of time of up to three weeks. An IC may also make costs orders against the complainant if the matter is dismissed for being frivolous or vexatious. This will go some way to deter and punish those who lodge unmeritorious complaints.

Introduction of a Review Committee

Presently, appeals against CC decisions are made to the Minister for Health. To enhance transparency and accountability and to avoid delays, a new Review Committee (RC) is introduced to review the CC’s decisions in place of appeals to the Minister. The RC will comprise one registered medical practitioner of at least ten years’ standing, one legal professional and one layperson. It will be limited to two specific situations:

- Due process reviews. The RC can make determinations on whether the CC has complied with due process, and can require the CC to comply with procedural requirement(s) that it failed to comply with.

-

The RC can direct a further inquiry or rehearing where the CC did not comply, or where new material evidence is submitted to the RC.

Improving quality and consistency of processes and outcome

The following amendments were introduced to improve the quality and consistency of processes and outcomes in the disciplinary process.

SMC to determine if matters should be referred to the Disciplinary Tribunal

Currently, a DT is appointed if the CC determines that a formal inquiry is necessary; the SMC has no role to play in this decision.

Under the new MRA, the ultimate decision as to whether a matter should be referred to a DT rests with the SMC.2 The CC will make recommendations to the SMC on whether there should be a formal inquiry. If a formal inquiry is recommended, the CC also has to formulate the charge and provide reasons for recommending the referral of the complaint to a DT. In assessing whether the threshold for a matter to be referred to a DT is satisfied, the CC and SMC should engage in the threestage inquiry set out by the Court of Three Judges in SMC v Lim Lian Arn:2

- First, establish the relevant benchmark standard applicable to the medical practitioner.

- Second, establish whether there has been a departure from the applicable standard.

-

Third, determine whether the departure in question was sufficiently egregious to amount to professional misconduct.7

Introduction of a Disciplinary Commission

A DC will be established under the new MRA to oversee the appointment and constitution of DTs, as well as their procedures and processes. This will be a separate body from the SMC, headed by a senior doctor as President. This replaces the current arrangement where the SMC, through the secretariat, assists in setting up the DT.2 In addition, the DC will oversee the training of members of the CP and Health Committees.

Disciplinary Tribunals to include legal professionals

Under the old MRA, there is no requirement for a legal professional to sit in a DT. Under the new MRA, DTs are to

comprise two doctors and one legal professional. In cases which may be more complex or raise novel issues of law, the President of the DC may apply to the Chief Justice to appoint a High Court Judge or Judicial Commissioner as Chairman of the DT. It is hoped that the introduction of legal professionals will bring greater legal and forensic expertise to the deliberations and determinations of DTs.2

Disciplinary Tribunal may appoint independent experts

To allow for more efficient and effective evidence, a DT may appoint independent experts, but are to first hear the views of the medical practitioner and the SMC. The DT may, instead of or in addition to appointing its own experts, allow the medical practitioner and the SMC to appoint their respective experts. This is for mitigating unnecessary acrimony in proceedings.8

Removal of minimum suspension period of three months

Presently, after an Inquiry, a DT may make one or more of the orders set out in the old MRA. This includes dismissal of the matter, imposition of conditions or restrictions on the medical practitioner’s registration, censure, imposition of a penalty not exceeding S$100,000, or imposition of a suspension term.

Under the new MRA, the minimum suspension period of three months is removed. This means that if the DT decides to impose a suspension term, it has the discretion to order a term of between one day and three years instead of starting with three months as a minimum.

We have in fact advocated for this change in a Singapore Medical Journal paper in 20129 and are pleased that this amendment has now finally materialised to give DTs more discretion in sentencing, which should result in fairer sentences for medical practitioners that are commensurate with their culpability and any harm caused.

Protecting patients more effectively

The following amendment has been introduced to protect patients more effectively.

Immediate Interim Orders for appropriate cases

An Interim Orders Committee (IOC) can make an immediate interim order without first giving the medical practitioner the right to be heard in certain exceptional situations:

- When a court of law in Singapore has made a finding that the medical practitioner has engaged in the conduct alleged in the complaint or information, and the conduct poses an imminent danger to the health or safety of any of the medical practitioner’s patients.

-

Where the SMC is of the opinion that such conduct poses an imminent danger to the health or safety of any of the medical practitioner’s patients.

These are high thresholds and should be exercised exceptionally in the interest of patient safety and public interest. After such an immediate interim order is made, the IOC must convene a hearing within one month to hear the medical practitioner’s position, failing which the immediate interim order will cease to have effect.

Amicable resolution of complaints in a less adversarial process

To encourage the amicable resolution of complaints and facilitate a less adversarial disciplinary process, in line with the Workgroup’s recommendation for enhanced use of mediation, an IC or a CC may, at any time after a matter is referred to it but before the completion of its inquiry, refer the matter for mediation. The relevant inquiry may be suspended when mediation is ongoing. Relatedly, an IC or CC may, when determining costs, take into account the parties’ conduct relating to mediation.

Other structural changes

Although not reflected as an amendment to the MRA, the SMC will establish a Legal Advisory and Prosecution Unit to introduce greater legal support throughout the disciplinary system and improve the quality of decision-making. Specifically:

- The Legal Advisory arm will advise the various committees in their disciplinary framework and provide legal support for these committees.

-

The Prosecution arm will be a dedicated in-house prosecution team that conducts prosecutions for the SMC, replacing the current system whereby the SMC engages a panel of external solicitors in private practice to conduct prosecution on its behalf. It is envisaged that this will improve consistency in how charges are framed, and the factors to be taken into account for mitigation or aggravation (as the case may be).2 Not to mention substantial reduction of prosecution’s costs charged by private law firms which are currently borne by medical practitioners (or their professional indemnifiers) upon being convicted of disciplinary offences.

Concluding comments

The new disciplinary process is a welcome change. It is hoped that with the new MRA, complaints can be disposed of more expeditiously, addressing the existing backlog of cases. It is also hoped that frivolous and unmeritorious complaints get filtered out early, thereby preventing doctors from being unduly vexed by unnecessary disciplinary proceedings.

It was commented during the Parliamentary debate that the best way to help patients is to help doctors help patients.10 The amendments can help to ensure high standards of quality and safety in the healthcare system by balancing the various interests, and providing both protection and adequate recourse for aggrieved patients and their families.

The reform of the SMC disciplinary process was long overdue. In 2013, the SMC also conducted a review of the

disciplinary process after the old MRA came into effect in 2010. In retrospect, that review – which did not engage the medical fraternity as widely as the Workgroup did in 2019 – missed the opportunity of addressing in depth the root causes of the problems identified by the Workgroup, which had always beset the process. In contrast, the amendments in the new MRA, which have legislative force, are much broader in scope and took on-board invaluable feedback of the medical community following intensive engagement of stakeholders. This experience indicates that wide and intensive consultation with stakeholders is absolutely necessary for real positive change.

While the steps are no doubt in the right direction to restore public and professional trust and confidence in the

SMC disciplinary process, it is still early days to tell the extent to which the new MRA will in fact resolve the various concerns of the medical profession. Time will be the best litmus test. But it is probably not an overstatement that the new MRA represents the collective will and effort of a united medical profession working together with a responsive Government to recreate a fairer, efficient, more effective and robust disciplinary framework for doctors, which can only benefit the profession and the public.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Mr Chan Yuk Chi, trainee solicitor at Donaldson & Burkinshaw LLP, for his editorial assistance and contributions to this article.