Riding on the coattails of a fresh email thread titled "Green Committee Kick-off Meeting", a handful of individuals gathered in the psychology department meeting room. Our common purpose was to brainstorm ideas to increase awareness of the urgency of the climate crisis on the hospital campus.

The mantra that anchored our first meeting was to "start small and just get the ball rolling". In conjunction with Earth Day, a week–long's worth of activities swiftly followed to encourage both the staff and public to contemplate their relationship with Mother Earth. This jumpstarted the green movement many of us had been hoping for within the Institute of Mental Health.

Subsequent activities continued to be offered through 2019, culminating in recent discussions with senior management about larger systemic changes we could implement hospital-wide, beginning with the removal of single-use plastics (see Figure 1).

While the Green Committee comprised of nominated individuals, we prided ourselves as a group that was completely voluntary, made out of a serendipitous mix of psychologists, medical social workers, pharmacists, nurses, administrators and doctors with diverse environmental ideologies. With a common goal to advocate for the plane and shed light on the climate crisis, the members are now referred to as "The Planeteers" within the hospital.

Returning to the heart of healthcare

"First, Do No Harm". While the aged dictum has been subjected to debates over the years, it remains symbolic in medicine, upholding healthcare's principles of non-maleficence and beneficence, and a respect for human rights. Now, what if we told you that we have all failed as healthcare professionals – that we have not been upholding the most rudimentary principle of medical ethics?

Recognising healthcare's significant climate footprint

Ironically, as an industry whose main prerogative is to protect and promote health, we contribute significantly to the present climate crisis. According to a paper published by Health Care Without Harm and Arup in 2019, 1 we are responsible for 4.4% of global net emissions (equivalent to 514 coal–fired power plants). Taken as a country, the healthcare sector would be the fifth-largest emitter on the planet!

At the heart of our emissions is our consumption of fossil fuels, driving more than half of healthcare's carbon footprint across the spokes of energy, transport, pharmaceuticals, product manufacture, purchase, use and disposal. Yes, the same things that are positioned to heal our patients are also contributing to the pathway leading to their demise.

The impacts of the climate crisis on human health

Our dependence on fossil fuels is radically changing the natural world and while some may view climate crisis as merely an environmental problem that has distal impact on our lives, The Lancet has deemed it the "biggest global health threat in the 21st century".2

We have witnessed the ravages of global warming at the turn of the new decade. These include being in the middle of the sixth mass extinction to raging wildfires engulfing Australia resulting in severe impacts on biodiversity, economic and public health;3 warm spells and record-high temperatures observed in Antarctica since November 2019;4 ,5 flash floods in Jakarta in January this year;6 locust plagues in East Africa in February;7 and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Frighteningly, we have barely scratched the tip of the iceberg.

Many have declared that Earth is in a state of climate emergency,8 and the pattern of rising temperatures will continually change our ocean and atmospheric chemistry. This will result in more extreme weather events with accompanying physical and mental health traumas and mortality. We can expect more aggressive spread of infectious diseases which are climate-sensitive or carried by vectors, like cholera, malaria and dengue.1,9 Higher reports of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases are also expected with increasing air pollution.1,9 Further, with the invariable impact to agriculture production and access to potable water comes malnutrition, gastrointestinal disorders, the threat of food and water security, migration issues, civil conflict, economic and ecological collapse, and associated long–lasting mental health impacts.1 ,9 ,10

Climate crisis and human rights

Public health issues aside, the climate crisis is also a magnifier of inequality. Some of Singapore's accolades include being one of the world's richest countries,11 as well as ranking sixth globally for consumption–based emissions according to the Global Carbon Atlas.12 The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's carbon target for 2030 is 2.82 tonnes per person. At present, the average Singaporean consumes a whopping 20 tonnes per person, more than four times the present world average. A study conducted by Oxfam13 reflects that the wealthiest 10% of the global population is responsible for 49% of total lifestyle consumption emissions, while the poorest 50% of the world's population contribute just a mere 10%. It revealed that the effects of the climate crisis impact both the rural and urban poor as well as females more disproportionately, as they often depend on natural resources and climate for income and food, or might live in places that lack the resources and infrastructure to mitigate and manage crises. While Singapore might have the resources to adapt to the climate crisis, a just and moral question ought to be whether we are doing enough as a nation to mitigate and reduce our contribution to the climate crisis.

Our influence and duty as healthcare workers

In this vein, as healthcare workers, our duty surpasses the walls of our clinics and hospitals. Advocating for the health of our patients would also entail being stewards to our environment – the places where our patients reside. Fortunately and uniquely, our voices have been shown to carry weight in our wider community in humanising climate change and spurring effective behavioural change.2,14

As individuals and as a profession, we could start by reflecting on our values (eg, health, justice, family and food) and how this is impacted by the climate crisis. The subsequent steps are simple – be mindful about your consumption and speak up about it in your families, teams at work and community (eg, health talks and its relationship with climate change). When done collectively, our voice adds volumes to the severity of climate change and encourages others to emulate.

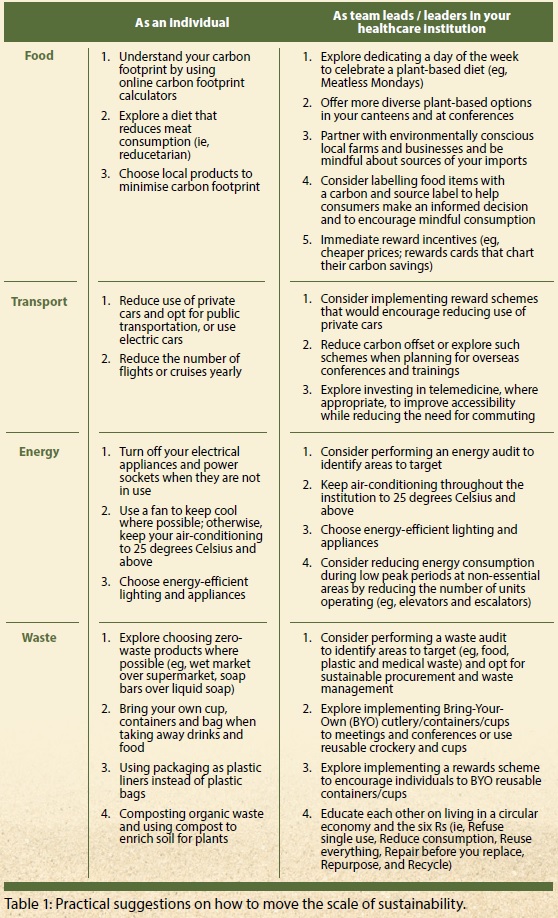

In our institutions, give voice to and make sustainable practices part of the core values (eg, joining and supporting Global Green and Healthy Hospitals to exchange resources and work cohesively as a sector to advocate for better environmental health). How and what we consume as a sector will cascade down the supply chain and challenge the current status quo and our dependence on fossil fuels; for example, by committing to divesting from fossilfuel companies and opting for local, sustainable and environmentally conscious businesses. Table 1 provides some practical suggestions (not exhaustive) to get us started.

Collectively as a sector, we need to increase our dialogues with government representatives starting with Members of Parliament for where we reside and work, and local climate change advocates. We need to communicate public health issues related to climate change and call for rapid nation–wide decarbonisation, a rewilding and protection of our natural spaces and biodiversity, funding for climate–related research and collaborations with neighbouring countries to mitigate the climate crisis.

As Martin Luther King Jr once said, "The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice." How would you like to use your voice to demand for a just and liveable future for us and our future generations?