In 2013, I wrote a piece for SMA News, entitled "In the Line of Fire" (https://goo.gl/ggNBcK), on abusive behaviour towards healthcare workers (HCWs). It grew out of my personal observations in the emergency department of how patients and their relatives, when under stress, physically or verbally lash out at HCWs, sometimes using xenophobic and racially motivated comments as weapons to inflict greater hurt.

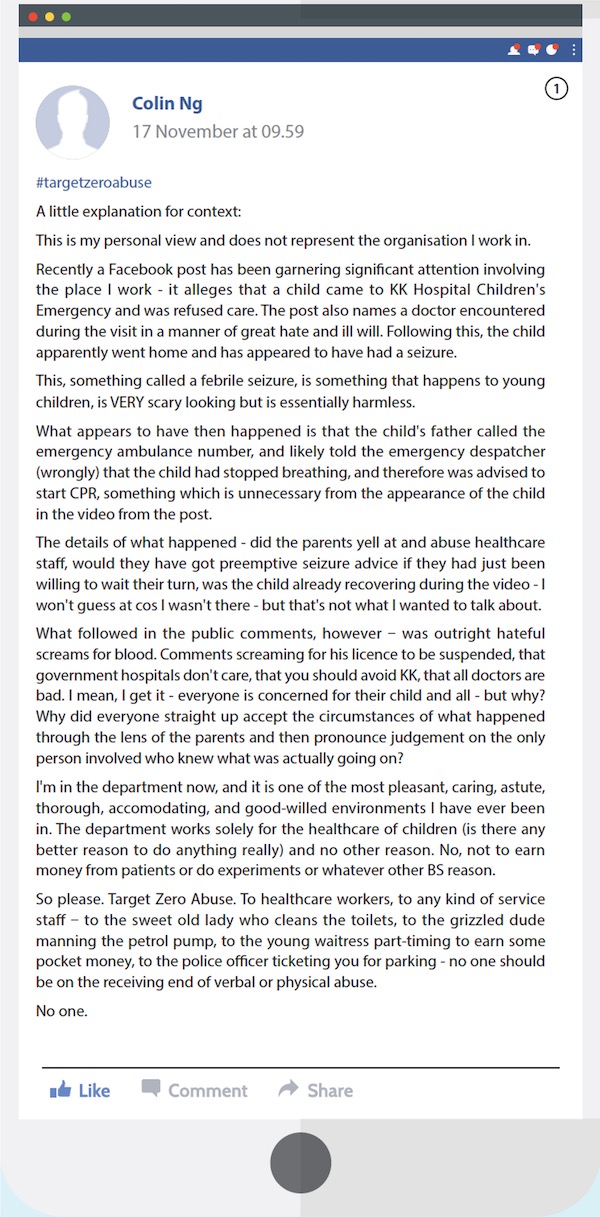

Since then, the rise of social media has become a new avenue for violence against HCWs. In a recent incident, a well-respected senior consultant in KK Women's and Children's Hospital (KKH) was accused by the parents of a young child of not providing timely care. This led to an outpouring of solidarity, with fellow HCWs sharing the #targetzeroabuse hashtag. A few of my colleagues spoke up in posts of their own, one of which is reproduced on the next page. The timely clarification of medical issues, picked up by some alternative news sites, helped to redress some of the balance of public opinion. KKH issued a formal statement a few days later to clarify that there were no lapses in medical care or patient safety.

The faceless mob

When I first read about mobbing, as a child reading animal stories, it was in the context of starlings mobbing a hawk. Birds who recognise a predatory species gather in large numbers to harass the predator, drawing attention to it and driving the predator away.

Unfortunately, mobbing is becoming a human phenomenon seen increasingly on social media. Outraged netizens cast themselves in the role of the vigilante righting a wrong, publicly defaming or harassing their target in an index post, gathering a mob. The problem is that, unlike in the animal world, it is difficult to say who the predator or prey is. Keyboard warriors do not usually have the full picture before the bloodbath begins. A good name can come under undeserved attack by cowardly bullies.

Let's make no mistake: a social media attack is unequivocally a form of workplace aggression. An editorial published in the Annals Academy of Medicine in November 2015 estimates that up to seven in ten of Singapore's hospital staff have experienced physical abuse, with significant under-reporting.1 The same commentary points out that workplace aggression is "not limited to physical violence, or to the geographical worksite, [but] is any abuse, including verbal, physical or emotional abuse and sexual harassment of healthcare providers resulting in injury, psychological harm, mal-development or deprivation."

Indeed, an online attack that accumulates manifold hurtful jibes from a hundred different sources may be more intimidating than a "real-life" confrontation. Particularly when the original attack is founded on a misunderstanding which one is powerless to address, the faceless multitudes can have their say while the HCW involved is bound to patient confidentiality and can say nothing in his/her own defence.

Institutional solidarity is essential

As HCWs in this day and age, it is surely a matter of "not if, but when" that each of us will be subjected to a similar trial. What then is our recourse for social media harassment?

Firstly, at an institutional level, the Workplace Safety and Health Council recommends a hazard management system to deal with cases of workplace aggression, which should include a clear policy known to and understood by management and employees, and management committed to a violence prevention programme.2 While not straightforward to implement in the context of online harassment, the same principles apply. In order to have the peace of mind to go about our daily duties, we need the reassurance that our institutions will always stand up for us should we come under attack for doing our job.

Secondly, legislation against cyber-harassment in Singapore takes the form of the Protection from Harassment Act3 that was introduced in 2014. While there have been no publicised cases of this being used by a HCW, it may be only a matter of time before a case arises to demonstrate that there are indeed punitive consequences for cyber-bullying.

As HCWs practising compassionate medicine, our attitude to experiencing workplace aggression is twofold. While we must recognise that harassment is never an acceptable "part of the job", we do understand that bad behaviour often comes from a place of anxiety and fear. Often, individual HCWs are not vindictive; they are keen to shake off the incident like water off a duck's back, provided that the incident does not cause lasting wounds. "Good prognostic factors" in our response to an incident include timely institutional and peer support, a sense of purpose, a clear conscience and a willingness to forgive. However, a magnanimous individual response to harassment can only exist when coupled with the solidarity of fellow HCWs against bullies and an institutional policy of zero tolerance for HCW abuse.