Recent cases in the newspapers have shown that it is increasingly important for doctors to have a firm understanding of (a) their ethical obligations and (b) their legal duties to their patients. This is the first of two articles that focus on the doctor's legal duty to exercise reasonable care. The first article will explain and illustrate the new test for medical negligence. The second will explore the practical differences between the old and new tests.

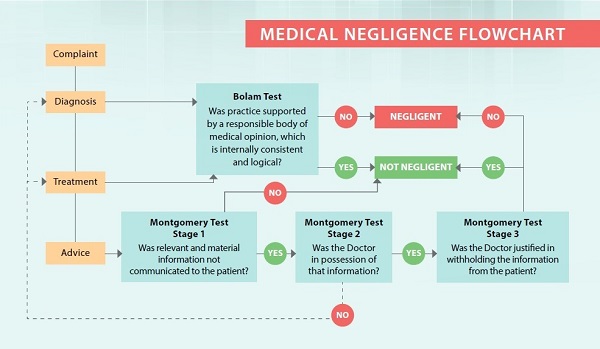

For a quick summary of the present legal position, please see the appended flowchart.

Introduction

Most doctors will be aware of the legal test for medical negligence: the Bolam test (as it is commonly known).1 Under the Bolam test, a doctor will not have acted negligently if the act complained of is supported by other respected doctors, so long as those doctors' opinion is internally consistent and logical (also known as the Bolitho qualification).2 It does not matter if those doctors happen to be in the minority.

For many years, the Bolam test applied to all aspects of a doctor's practice: ie, diagnosis, advice and treatment.

But things have changed after the recent Court of Appeal decision in Hii Chii Kok v Ooi Peng Jin London Lucien.3 Now, the Bolam test applies to determine only whether a doctor has been guilty of negligent diagnosis or treatment. A new legal test applies to determine whether a doctor was negligent in advising the patient: the "Montgomery test".4

When does the Montgomery test apply, what does it entail and why does it apply only to giving of advice? This article will answer those questions.

Diagnosis, advice and treatment

The patient-doctor interaction may include:

a. Diagnosis: the identification of the patient's affliction. Diagnosis is the process by which the doctor obtains information from the patient by taking history and physical examination, considering what further investigations are required, analysing the information and forming a provisional conclusion on what to do.

b. Advice: the presentation of the appropriate information to the patient. Advice includes giving recommendations on what should be done, providing information on diagnostic procedures and any associated risks, as well as advising treatment plans and associated risks.

c. Treatment: the implementation or execution of the cure, including medication, surgery or other procedures.

A doctor may be negligent in his diagnosis of, advice to, and/or treatment of a patient. A doctor may misdiagnose a cancerous tumour as a benign one, wrongly explain what side-effects a particular drug may have, or make a mistake during surgery by amputating the wrong leg.

Historically, medical negligence law did not distinguish between diagnosis, advice or treatment. In all cases, the Bolam test would apply. That has now changed.

In Hii Chii Kok, the Court of Appeal said that the Bolam test would continue to apply to diagnosis and treatment, but that a new test for negligence would apply to the giving of advice. This new test was called the Montgomery test, after a UK Supreme Court decision.

The reason for this change was the shift towards a more patient-centric approach to medicine. In particular, a patient should have the freedom to make an informed choice about what medical treatment (if any) he/she undergoes. In this regard, the Bolam test was outdated. The Bolam test was created in the 1950s when medical treatment was paternalistic: doctors would simply prescribe their professional view, which the patient was expected to accept unquestioningly. The court said that such a paternalistic approach was inconsistent with the modern day emphasis on "informed consent". So a new test was needed for cases where doctors gave advice to their patients.

The Montgomery test

A patient receiving advice is not simply a passive recipient of care (as one would be when one's ailment is being diagnosed and treated). The patient plays an active role because ultimately the patient should decide on the course of treatment (if any); and the patient can make an informed judgement only if he/she has sufficient advice and information. The crux of the Montgomery test is whether the doctor has given the patient sufficient advice and information.

What is sufficient advice and information? This is a question that will be determined by the court objectively: what would that particular patient in his circumstances reasonably regard as material? The sufficiency of the advice and information will not depend solely on the views of other respectable doctors (as it would have under the Bolam test).

The Montgomery test will be applied on the facts and circumstances as they existed at the time the material event occurred. The Montgomery test has three stages:

- The patient must satisfy the court that relevant and material information was withheld from him.

- If yes, the court will determine whether the doctor had that information in the first place.

- If yes, the court will determine whether it was justifiable for the doctor to withhold that information from the patient.

Each of these stages deserves closer attention.

Stage 1 of the Montgomery test

Stage 1 of the Montgomery test asks whether the patient failed to receive any relevant and material information. Doctors ought to disclose (a) information that would be relevant and material to a reasonable patient in that particular patient's position; and (b) information that the doctor knows is important to that particular patient in question.5

The relevance and materiality of information is assessed essentially from the perspective of the patient. Relevant and material types of information would include (but are not limited to):

(a) the doctor's diagnosis;

(b) the prognosis with and without medical treatment;

(c) the nature of the proposed treatment;

(d) the risks associated with the proposed medical treatment; and

(e) the alternatives to the proposed medical treatment and their advantages/risks.6

The court will apply a common-sense approach to determining whether specific information was relevant and material. Doctors will have to walk the fine line between:

(i) taking reasonable care to ensure that the patient receives all relevant and material information – failing which the patient would be unable to make an informed decision; and

(ii) not indiscriminately bombarding the patient with every iota of information – failing which the patient may simply be left more confused and also unable to make an informed decision.

For example, say a patient is contemplating a particular surgical procedure, which carries with it a number of risks. A doctor does not have to disclose each and every possible risk to the patient. Whether a risk has to be disclosed depends on the severity of the potential injury and its likelihood. Hence the risk of a likely but slight injury should be disclosed; and so will the risk of an unlikely but serious injury. But importantly, the risk of a very severe injury would not have to be disclosed, so long as the possibility of its occurrence was "not worth thinking about" – eg, because the likelihood of its occurrence is negligible, or because such a risk is common knowledge.7

To take another illustration, a doctor will have to tell the patient about the benefits and side-effects of the proposed medical treatment. The doctor must also tell the patient about the advantages and disadvantages of alternative procedures, and the consequences of having no treatment at all. But the doctor only has to tell the patient about reasonable alternatives – ie, the doctor does not have to tell the patient about fringe alternatives or treatments that are obviously inappropriate.8

Further, a doctor must disclose information that he knows (or ought reasonably to know) would be important to that particular patient.9 For example, when a doctor is taking a patient's history, he will commonly find out the patient's occupation. That knowledge may be important in assessing what information that particular patient would find material and relevant. Hence a very low risk of slight eye injury would be highly relevant to a professional fighter pilot, even if it might be insignificant to other people.

The doctor does not have to ensure that the patient in fact understands the information provided, but only to take reasonable care that he does.10 So while the doctor does not have to "test" the patient's knowledge, the doctor will have to assess the ability of the patient to understand the information. The doctor will have to deliver the information using language and at a pace that allows the patient to absorb. Understanding means that the patient must appreciate the significance of the information – hence simply reciting to the patient the statistical probabilities is unlikely to be enough.

Stage 2 of the Montgomery test

Stage 2 of the Montgomery test asks whether the doctor did in fact have the information (that was relevant and material, and not told to the patient).

If the doctor did not have the information, he cannot be negligent for failing to provide that information to the patient. But he could potentially be negligent for not having that information in the first place – ie, negligence in diagnosis (because certain investigations were not done) or negligence in treatment (because the doctor did not realise an alternative treatment was available).

Whether or not the doctor was negligent (in diagnosis or treatment) for not having had the information in the first place will continue to be determined by the Bolam test.

If the doctor did have the information (but did not tell it to the patient), we go to stage 3 of the Montgomery test.

Stage 3 of the Montgomery test

The last stage of the Montgomery test asks whether the doctor was justified in withholding the information from the patient – ie, was it a sound judgement that a reasonable and competent doctor would have made? If yes, the doctor is not negligent, and vice versa.

The burden is on the doctor to justify why the doctor withheld reasonable and relevant information that he knew about (as established at stages 1 and 2 of the Montgomery test) from the patient.

In general (with the exception of (b) below), the focus is not on whether other respectable doctors would have considered it appropriate to withhold that information (ie, the Bolam test will in general not apply), but on whether it was objectively reasonable in the circumstances to have done so.

Here are some examples of when nondisclosure of information would be justified:

(a) Consent: where the patient has expressly said (or it can very clearly be inferred) that he does not wish to hear further information.

(b) Emergency: in emergency situations where there is a threat of death or serious harm to the patient, the patient temporarily lacks decisionmaking capacity, and there is no substitute decision-maker.11

(c) Therapeutic privilege: where the doctor reasonably believes that giving the patient that information would cause the patient serious physical or mental harm (eg, patients whose state of mind, intellectual abilities or education may make it extremely difficult to explain the true reality to them).

The interplay between the Bolam test and the various stages of the Montgomery test is summarised in the flowchart on page 29. The next article will look at the practical differences that arise between the Montgomery and Bolam tests.