When I was a trainee in family medicine back in Japan, I observed that many doctors seemed to consider their role as one who treats and cures patients' diseases as fast as possible. Hence, they paid less attention to palliative care and some even felt that palliative care was not part of a doctor's job scope. To tell the truth, this is still a reality in Japan despite the percentage of cancer-caused deaths reaching 30%. As many doctors are trained as specialists with the purpose to save patients' lives, it may be reasonable for them to argue their case as such.

However, when it comes to a situation where patients are in the progressive states of illness and there is nothing much more to be done, the change in their doctor's attitude towards treatment may come to them as a shock, and patients may be disappointed with such attitude and complain that their attending physicians have given up on them.

Things do not end there. Given that the role of doctors is to perform the surgery as part of treatment, once the doctor considers the patient's lesion as unsuitable for the operation, or that chemotherapy or radiation therapy is not suitable for the patient's condition, they lose their role.

Aspects of palliative care

Recently, many health professionals have emphasised on the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to providing patients with appropriate healthcare and welfare intervention. However, doctors working in a hospital are generally less interested in this aspect and would leave this responsibility to allied health workers and community doctors. After seeing such situations during my home visits for a terminal stage patient, I elected to do two months of training in a palliative care ward, aiming to provide better palliative care to my patients and to teach it to our juniors.

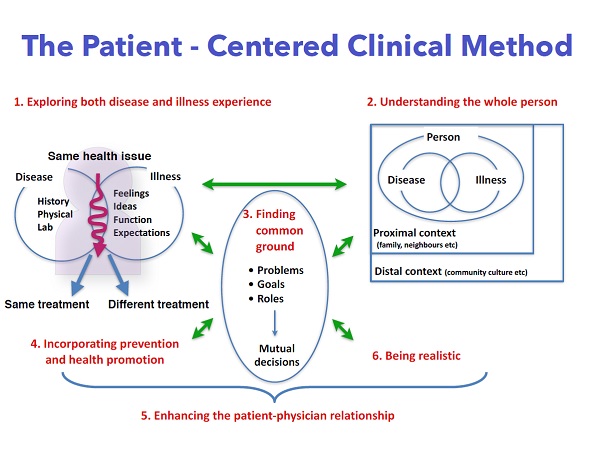

As you may have realised, family medicine and palliative care share a high affinity with each other. For example, family physicians in Japan usually use patient-centred clinical methods during the consultation (see Figure 1). This is because when it comes to health problems, we take not only the disease aspect (eg, biomedical points of view such as history, physical condition and laboratory testing) but also the illness aspect (eg, feelings, ideas, function and expectations) into consideration.1

Figure 1.

The consultation by a specialist is usually approached from the disease aspect, so they value history-taking, physical examinations, and laboratory tests and imaging. Of course, such an approach is important for all doctors and is necessary for all consultations.

However, regardless of the degree of their symptoms, many patients showcase the aspect of illness, such as a fear of, a pessimistic or optimistic view on, and excessive expectations of their condition. These feelings are easily wavered and affected not only by tiny changes in their condition but also proximal contexts (eg, family or relatives) and distal contexts (eg, cultures or habits of their region).

After understanding the illness aspect and how it affects a patient's emotions, family physicians can propose the type of end-of-life care that is acceptable to the patients and their family members. Sometimes, not just the patient but the family member may also request for something beyond what is expected.

Instead of declining such wishes and passing them off as unrealistic, we should dig deeper into the hidden meanings behind the requests, seek common ground and find feasible solutions through collaboration with a multidisciplinary team.

What is most important is that these patients and their family members only have very little time left to share. Once they miss the opportunity, they can never again afford it. This is why health professionals should have the ability to respond promptly to such requests.

When it comes to palliative care, many doctors tend to focus on pain control, symptom control and counselling. However, the role of doctors who work at hospices or palliative care wards differs from doctors who see patients with palliative care need in a community. Compared to the hospitals, medical resources in the community may be lacking. Therefore, family members have to play the roles of health professionals all day long. Besides counselling patients, evaluation and support to ease the burden of care of family members is important during home visit by family physicians.

Another characteristic of palliative care by family physicians is the continuity of care. Because family physicians do not only see patients who need palliative care, they have the opportunity to see also their family members or relatives during the process of building patient- doctor relationships. Such a wide range of continuity of care is one of the attractive points of being a family physician and is a precious experience for us.