Singapore's maternal and child health (MCH) system plays a crucial role in ensuring the well-being of mothers and children, shaping the health of future generations. In this rapidly evolving landscape, evidence-based guidelines serve as essential tools for improving health outcomes and addressing emerging challenges.

New MCH challenges, old care models

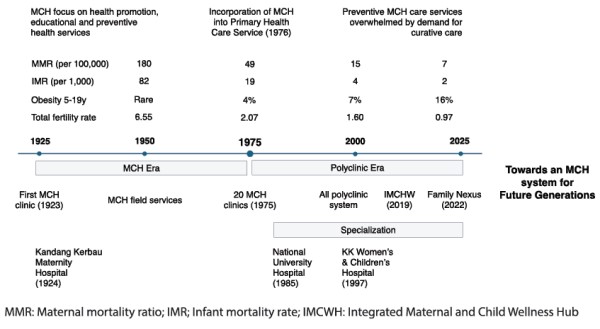

As the landscape of healthcare evolves, so must our approach to MCH. Yet, a look at the MCH system in Singapore over the past century reveals two distinct divisions – one where MCH grew and thrived, and another where it weakened following its embedment into the polyclinic system (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Two faces of Singapore's maternal and child health system

The golden years of MCH care were established at a time of high maternal mortality, aimed at addressing haemorrhage, trauma, sepsis and high infant-child morbidity, particularly communicable diseases and malnutrition. During this half-century, the Kandang Kerbau Hospital became a maternity hospital (1924), and the first, second and third dedicated MCH clinics opened their doors in Prinsep Street (1923), Kreta Ayer (1924) and Joo Chiat (1931), respectively. More MCH clinics followed, reaching a total of 20 by 1975. While the system treated minor ailments, its core focus was on preventive care, providing services such as well-baby clinics, immunisation, developmental screening, family planning services, antenatal and postnatal care, and home nursing care.

Two significant changes transformed the MCH model of care after 1975. The first was the establishment of the primary healthcare services of the Ministry of Health in 1976, which merged the field of MCH with outpatient services, family planning, school health, and training and health education. In a 1980 review on Singapore's MCH services, Dr Dolly Irene Pakshong, the MCH medical superintendent, noted the rising trend in sick child attendances at MCH clinics and warned that "health promotion, education, and preventative services could be swamped by the insatiable demand for curative services".1

Her observations were prescient as a second key change in the MCH system followed, and Singapore witnessed a growing demand for specialty institutions. The establishment and development of various departments of O&G and of paediatrics in Singapore, followed by the KK Women's and Children's Hospital (KKH) in 1997, heralded the era of specialist care.

While these changes have had their benefits in advancing the care of diseases in tertiary settings through investments in technology, infrastructure and manpower development, there were unintended consequences. These included increased reliance on subspecialisation, reduced access to postnatal maternal care and missed opportunities to develop preventive services to address present-day challenges.

Addressing MCH challenges

In recent years, Singapore has faced significant MCH challenges, marked by a sharp rise in metabolic disorders, non-communicable diseases, obesity and an alarming prevalence of mental health issues among perinatal women.2 The current polyclinic system is strained amid the focus on an ageing population and the demand for curative care. The loss of emphasis on community MCH matters, compounded by the development of centralised obstetric and paediatric care, underscores the urgent need for renewal. While advancements in tertiary care are valuable, we need to reprioritise the MCH system to address contemporary metabolic and mental health challenges more effectively from their foundational origins.

The Integrated Platform for Research in Advancing Maternal and Child Health Outcomes, one of the main programmes by the SingHealth Duke-NUS Maternal and Child Health Research Institute, has been leading the development of guidelines aimed to bring MCH care sharply back into focus. Each of the guidelines are key components of the Healthy Early Life Moments in Singapore model of care, an interactive and personalised approach to engage, support and guide women through the most crucial period of developmental opportunity from preconception, pregnancy and early postnatal life until the child reaches 18 months of age.

The effectiveness of the guidelines can be best gauged by their successful implementation in community settings. Key collaborators in this endeavour include the Family Nexus, a community health programme dedicated to integrating health and social services for families with young children, and the Integrated Maternal and Child Wellness Hub at Punggol. These evidence-based programmes offer comprehensive support, including developmental screening and vaccination for children, as well as maternal mental health screening, and emotional and lactation support.

Additionally, there is potential for the guidelines to serve as the cornerstone of a digital platform, offering comprehensive resources for parents and caregivers. By leveraging technology, we can disseminate vital information on healthy practices, eating and developmental milestones, and preventive care measures, empowering parents to make informed decisions for their children's well-being.

Seven MCH guidelines and counting

Beginning in 2018, the guidelines on managing gestational diabetes mellitus offer standardised protocols for screening, diagnosis and management, ensuring healthier outcomes for mother and child by mitigating the risks associated with unmanaged gestational diabetes.3 Progressing to 2019, another set of guidelines emphasises optimal perinatal nutrition, laying the groundwork for balanced diets during pregnancy and lactation. By educating mothers on nutrient-rich foods and appropriate supplementation, these guidelines foster the healthy development of the fetus and encourage lifelong health habits.4

In 2020, a set of guidelines promoting physical activity and exercise during pregnancy aims to enhance maternal fitness, alleviate discomforts and potentially reduce the risk of complications. This set addresses safety concerns, encouraging expectant mothers to engage in regular physical activity for their well-being.5 Transitioning to childhood, two sets of guidelines introduced in 2021 and 2022 provide recommendations for physical activity tailored to different age groups.6,7 By setting clear guidelines for daily activity levels and reducing sedentary behaviour, these guidelines combat childhood obesity and promote overall well-being from an early age. Addressing the often overlooked aspect of maternal psychological well-being, another set of guidelines launched in 2023 casts a spotlight on perinatal mental health, emphasising the importance of early detection, intervention and support systems for mental health conditions.8 By ensuring mothers receive necessary care, the guidelines benefit family units and their dynamics as well as child development.

More recently, the Singapore Guidelines for Feeding and Eating in Infants and Young Children was launched in February 2024 by Senior Minister of State Dr Janil Puthucheary at KKH. Designed for healthcare professionals and caregivers of children aged zero to two years old, these guidelines aim to cultivate healthy feeding practices and eating behaviours by providing goals and checkpoints as infants progressively transition from being fed to eating independently. These guidelines enhance the current infant care framework, which focuses on vaccinations and developmental assessments. By offering evidence-derived feeding-eating milestones in four main domains – variety, autonomy, setting and timing – the guidelines aim to establish early healthy feeding and eating habits. Given that habits formed in one's early years can endure for a lifetime and that 70% of obese children go on to become obese adults, early adoption of healthy practices can mitigate the risk of future metabolic disorders.

Conclusion

Revitalising Singapore's MCH system requires evidence-based guidelines, policy initiatives and community engagement. Effective implementation of the guidelines is crucial for improving MCH outcomes. By translating these guidelines into practice, we can tangibly improve health outcomes and foster a healthier society for future generations.