COVID-19 swept across the world with the force of a tsunami, devastating countless industries in its wake, wearing healthcare services thin and leaving the world scrambling to adapt to a new normal. As third-year medical students entering our clinical years, the pulse of uncertainty surrounding this pandemic was palpable. We are sure other medical students in Singapore can identify with our experience as we navigate this pandemic.

Impact of the pandemic on medical students

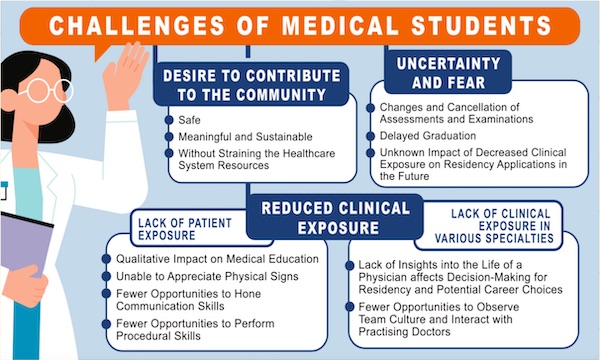

Clinical exposure has always been an integral and key area that equips medical students with skills to become a competent doctor.1 However, due to the pandemic, many schools have temporarily halted clinical postings and withdrawn students from hospitals to minimise the risk of exposure to COVID-19. In Singapore, students were immediately barred from the wards when the Disease Outbreak Response System Condition level Orange was announced. The temporary suspension and truncation of clinical postings left many of us uneasy, pondering its longterm implications. Firstly, reduced clinical exposure lessens our opportunities for patient interaction. Important skills such as communication with patients requires real-life practice to understand and grasp.2 Previously, a clinical posting would have presented us with many opportunities to take a detailed history from patients, allowing us to gain confidence and refine our communication skills.3,4 With the current restrictions, we now participate in alternative communication lessons by interacting with simulated patients in a safe environment.

Secondly, clinical postings would have allowed us to apply and reinforce pre-existing knowledge. Seniors have often mentioned that it is like witnessing textbook knowledge come to life. Active participation during ward rounds has also been shown to improve knowledge acquisition and retention.5 Learning basic procedural skills is similarly affected as precious opportunities to practise plug setting, insertion of urinary catheters and removal of drains are limited. Once again, alternative solutions such as simulation on mannequins have been implemented.

Furthermore, clinical postings are our first real glimpse of clinician life. Seniors fondly share memorable experiences, including their virgin experience scrubbing up for surgery, observing an endoscopic procedure being performed and surviving an overnight call. Currently, with aerosolgenerating procedures being deemed high-risk, operative experience and tagging on with house officers to clerk new cases in the emergency department is sorely lacking. Ultimately, experiences influence career interest in the relevant subspecialty,1,6 and may be an aspect where the pandemic has had an intangible impact on us.

Closer to our hearts, COVID-19 has also raised fear and uncertainty within the medical student community. Some students are in a dilemma – on one hand keen to resume clinical activities, but on the other hand worried about infecting their family and loved ones at home. It is crucial that we learn to manage our emotions and remain professional during this trying period, which will ultimately shape our professional identity in the future.7

At school, the landscape is also constantly evolving, including cancellation of clinical clerkship, postponement of assessments and delays in graduation. How would this affect our educational journey and career choices? Would there be a significant impact on residency placement?8,9,10 The questions remain unanswered and only time will reveal the pandemic’s impact on medical education.

In other parts of the world, it is heartening to learn that fellow medical students wish to contribute to the medical community. However, some share the view that medical students are not essential workers and them having direct patient contact would take a toll on precious resources such as personal protective equipment (PPE).11 Nevertheless, this should not deter medical students from contributing in safe, meaningful and impactful ways.12

Our surgical posting experience

We entered Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH) on the first day of our general surgery posting in June 2020 with mixed feelings – excited yet wary of the potential risk of exposure in a clinical environment. We were decked out in brand new scrubs, fresh-eyed and eager to begin our clinical journey, fully cognisant that we were living in unprecedented times. We were informed of restrictions on entering the operating theatre because of potential aerosol transmission and were unsure of how this would impact our clinical experience. How would we make the most of our truncated clinical posting? Would we unknowingly encounter a COVID-19 patient and infect ourselves? These were real and solemn questions that crossed our minds.

However, four weeks of surgical posting passed by in a flash with the flurry of activities planned for us and we completed the rotation safely and unscathed, dispelling many of our initial fears.

The general surgery department operated in the pandemic hybrid team system. We were each attached to one hybrid team consisting of surgeons from different subspecialties. As a result, we were able to appreciate a wide variety of clinical cases. Rotations to the specialist outpatient clinics provided further opportunities to examine patients and observe communication skills. We were also fortunate to meet many dedicated surgeons who conducted numerous tutorials to maximise our learning. Although we could not observe live surgeries, we were taught the concepts of surgical anatomy and the principles of surgery with technology-assisted learning (via surgical videos)

Our safety was emphasised with a pre-posting briefing on observing safe distancing and the appropriate donning of PPE. Constant reminders were also sent out to avoid designated high-risk clinical areas and to declare our temperature twice daily. We also had to log every patient encounter meticulously for contact tracing purposes. Despite the increased administrative tasks, the KTPH education administrative team was very helpful in facilitating this transition and in ensuring a safe and conducive learning environment for us.

After completing our clinical posting, we spent the rest of our original campus-based learning period participating in online tutorials from home, which provided a valuable opportunity for us to consolidate our knowledge from the posting as well as clarify any doubts that may have surfaced during this process. Some may lament the loss of precious clinical experience due to COVID-19; however, we were thankful to still have such a fruitful clinical experience during these uncertain times. Although we cannot steer the course of this pandemic, we believe that it is important for everyone to adopt a positive mindset and embrace every opportunity to learn and grow.

Final reflections

COVID-19 will continue to present medical students with more challenges in the immediate future. However, we are thankful that our local institutions adapted and rose to the challenge by embracing virtual and technologyassisted learning, with hospitals remaining dedicated to investing time in our clinical training. The silver lining in the pandemic lies in the wisdom and resilience forged during this trying time that will surely make us better doctors of the future.