Karoshi

Karoshi (過労死) – death (死: shi) due to overwork (過労: karo) – has been recognised in Japan for five decades. This phenomenon has since spread to South Korea and other Asian countries, and recently to Western countries such as France. Karoshi is the fatal outcome of overwork-related disorders, which are typically categorised into two groups: vascular (cerebrovascular/cardiovascular) diseases and mental disorders.

Work-related suicide or suicide attempts, known as karo-jisatsu (suicide from overworking), is a serious issue for families and the society. Karo-jisatsu is defined as the fatal outcome of workers who suffer from overwork-related mental disorders in Japan. If a worker could receive appropriate support and return to work after treatment, it would be beneficial not only for the worker and family members, but also for the employer and society. The indirect costs of suicide are much higher than the direct costs of supporting workers with suicidal ideations.

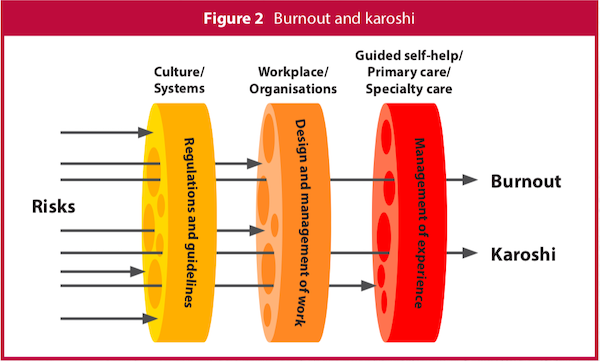

How do long working hours affect people's health and mental health? Data collected from workers' compensation certifications in 2016 showed that 80 hours or more of overtime per month clearly increases the number of cases of cerebrovascular/cardiovascular diseases (Figure 1). A recent meta-analysis confirmed that long working hours are associated with a high risk of cerebrovascular/cardiovascular diseases, especially stroke.1 The Japanese government has proposed capping overtime at 80 hours per month and this new limit could prevent overwork-related cerebrovascular/cardiovascular diseases in most workers. However, this might not address some overwork-related mental disorders because 39% of workers with mental disorders overworked less than 80 hours per month.

Mental health in overwork-related disorders

In 2014, the Research Center for Overwork-Related Disorders was established following the enactment of the Act on Promotion of Preventive Measures against Karoshi and Other Overwork-Related (Health) Disorders. Based on a summary of diagnoses among compensated cases of occupational mental disorders by gender over a five-year period, rates of mood disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and adjustment disorders in male (female) workers with mental disorders were 59.7% (27.0%), 10.6% (26.0%) and 16.6% (20.6%), respectively.2 More than half of the male workers had mood disorders, whereas PTSD was common in female workers. There are also reports of overwork-related physician suicides which are currently being analysed.

Physician burnout

Preventing burnout is another approach to reducing overwork-related disorders in clinical practice. Burnout is defined as a syndrome of physical and emotional exhaustion, reduced sense of personal accomplishment and depersonalisation towards clients.3 Burnout is highly prevalent in physicians (eg, 41% of physicians in stroke care in Japan experience burnout)4 and international studies have revealed that burnout is more prevalent in physicians than in the general population. Burnout can negatively impact a physician's well-being and professional career, and lead to increased rates of substance use, depression and suicidality. In clinical practice, physicians with symptoms of burnout are more likely to make major medical errors and engender lower patient satisfaction levels. In a study of 2,937 alumni of a Japanese medical university, urban hospital physicians faced greater job demands, less job control and higher incidences of emotional exhaustion caused by burnout, and rural hospital physicians had less social support.5 Physicians, particularly in "frontline" specialties, including general internal medicine, family medicine, emergency medicine and neurology, are at the highest risk of burnout.6

To reduce physician burnout, it is first necessary to assess the rate of burnout. Cognitive, behavioural and mindfulness interventions would help physicians. There is a review of self-care techniques to address burnout in Singapore,7 and recent meta-analyses suggest that organisational strategies can result in clinically meaningful reductions in burnout.8, 9

Conclusion

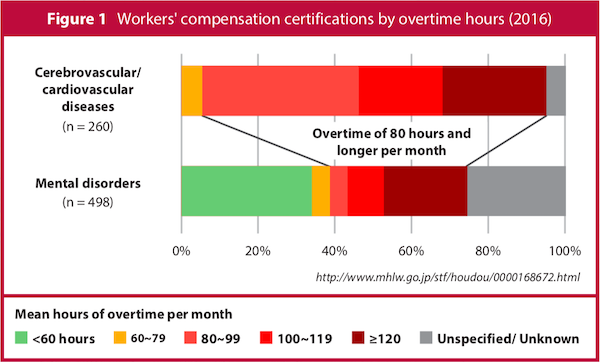

In clinical practice, karoshi, depression and burnout are overwork-related disorders. Specialised care is required in each specific case. Additionally, since burnout is related to quality of care and patient satisfaction, as well as wellness of the physician, individual organisations need to recognise that preventing and caring for those suffering from burnout is necessary to provide a high quality of patient care. Figure 2 illustrates preventive measures to reduce karoshi and burnout. The risks can be intercepted at cultural, organisational and individual levels. The Institute of Medicine's report titled "To err Is Human" has provoked patient safety movements since 2000. It is time to call for collective action for the well-being of physicians and to facilitate the best care for their patients, with the slogan of "To Care is Human".10